Central government is looking at whether councils should be allowed to borrow more, to build more

The current restrictions do need to change, said a spokesperson for the Department of Finance.

High buildings drive up construction costs and land values, some say, which means more expensive homes.

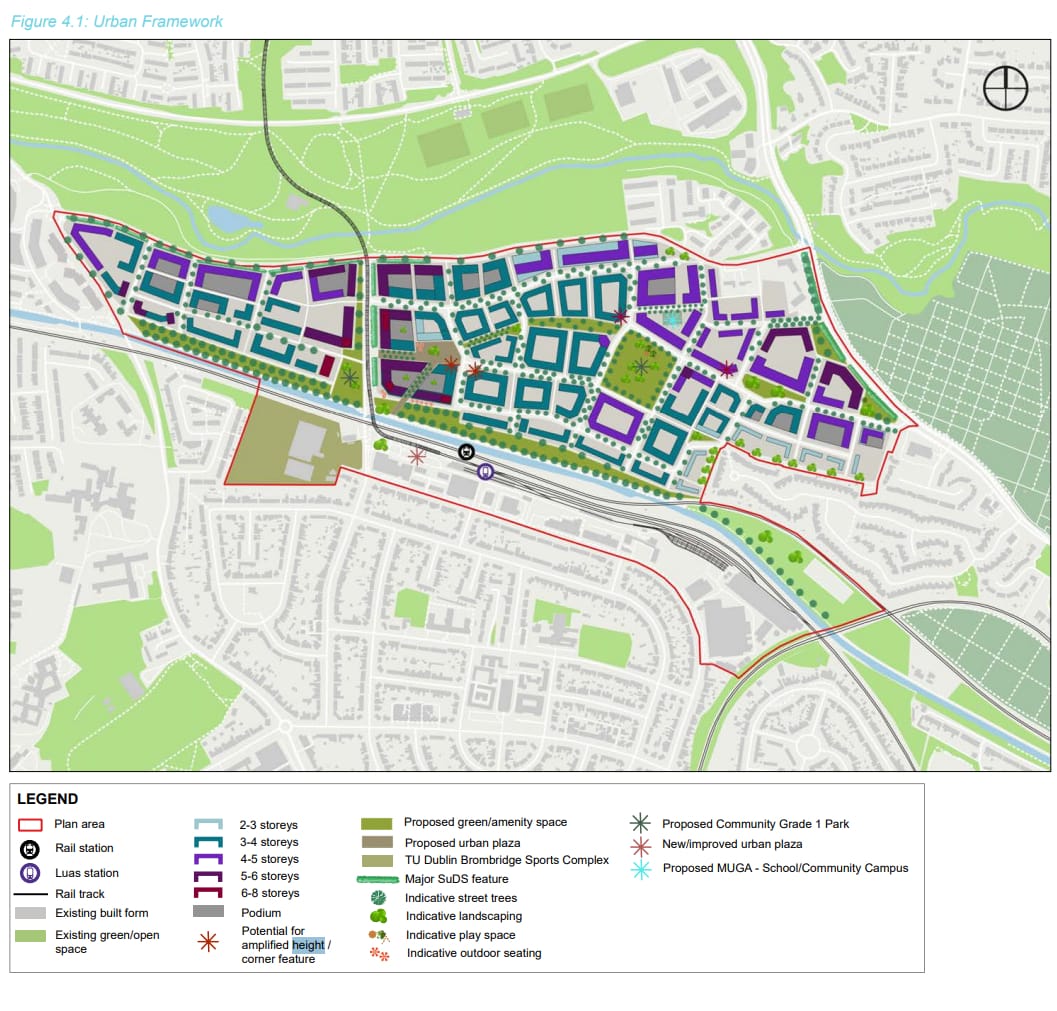

Dublin city councillors got sight on Tuesday of the latest changes to a draft masterplan for the massive tract of land at and around Dublin Industrial Estate, stretching a bit south but mostly north of Broombridge Luas stop.

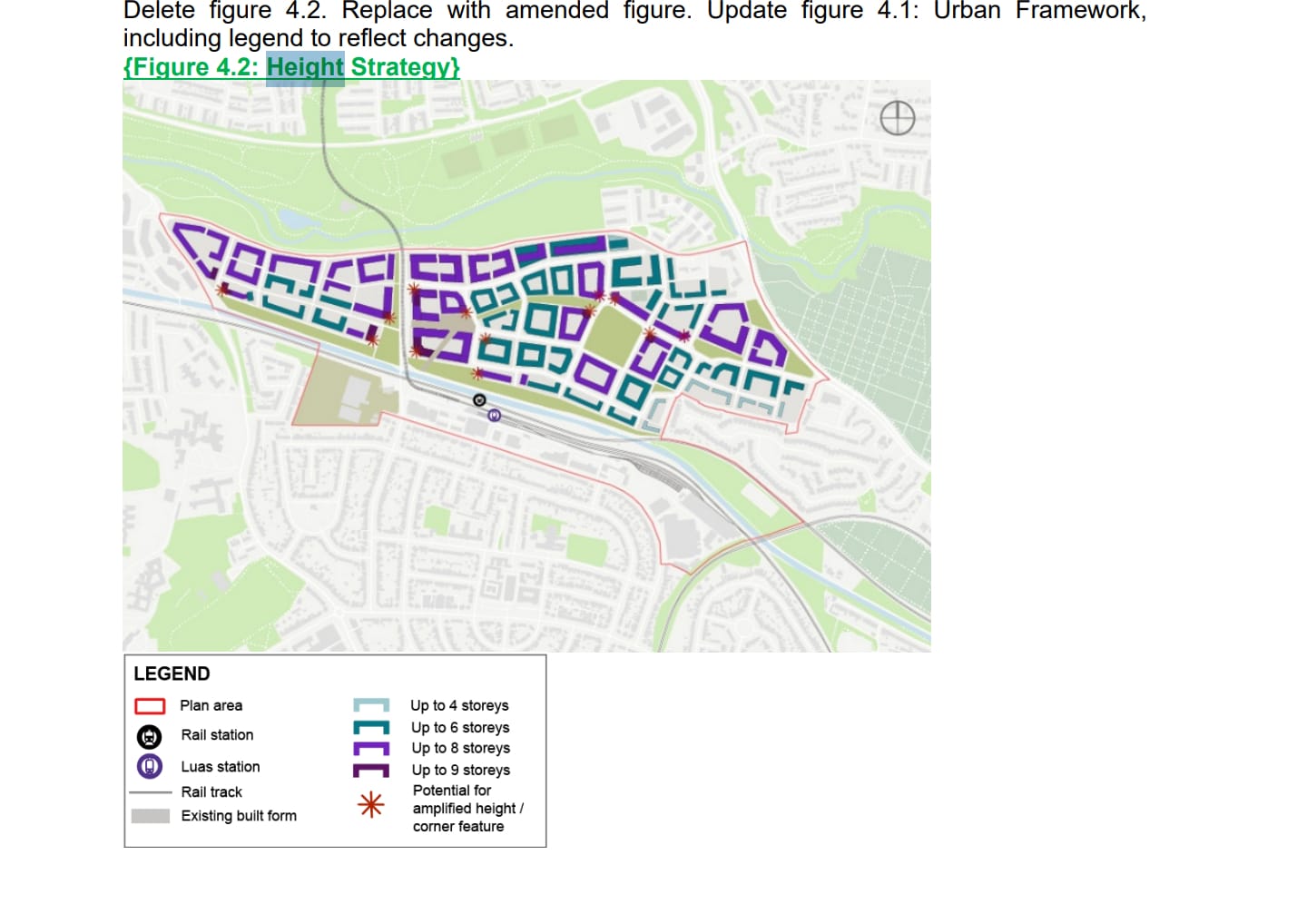

The new Baile Bogáin (Ballyboggan) Draft Masterplan will allow for taller buildings in more locations, shows a report from the Chief Executive Richard Shakespeare on submissions to the public consultation on the plan.

Local councillors at a meeting of the Central Area Committee on Tuesday agreed to the masterplan without much discussion. They had already had a private briefing.

The challenge with the Ballyboggan masterplan, as with other masterplans for industrial lands in the city, is hitting the sweet spot that takes into account density, compact development, and affordability.

Heights impact the prices of what is delivered and even whether anything gets built at all, says architect and housing commentator Mel Reynolds.

“High-rise apartments are very market-cycle dependent,” says Reynolds, referring to anything higher than six storeys. They are more expensive to build than low-rise, he said, and only viable right now in affluent areas and the city centre.

So some of the tallest buildings envisioned in the masterplan might never be built in that location, he says. And, homeowners can rarely afford to buy apartments in high-rises, said Reynolds, so they are likely to be snapped up by investors for rentals instead.

Low-rise and high-density are more economical to build, says Reynolds.

In April, it looked like that was what the Ballyboggin draft masterplan was aiming for. The council had recommended the majority of the plots of land there be developed with heights of up to 3 to 4 storeys in some places, or up to 4 to 5 storeys in others – while also designating some further spots as suitable for taller buildings.

But then that plan went out for a public consultation from when to when and got 144 submissions, from local residents, public bodies, landowners, developers and others.

After the public consultation was finished and the council rejigged the masterplan in response to the submissions, Richard Shakespeare, the council’s chief executive, issued a report which shows plots mostly up to six or eight storeys, with a few corners up to nine storeys.

But, curiously, the council hasn’t upped its range for how many homes could be built, from when the buildings were lower. The council hasn’t yet responded to queries sent Thursday as to why that might be.

Sinn Féin Councillor Séamas McGrattan said what kinds of homes may be built hasn’t really factored into discussions for the masterplan, because most of the land is in private ownership.

“It's only really density and height that you can control,” he says. “The tenure mix you can’t really control at this stage.”

The report on the draft masterplan will go to the full council next, says McGrattan, before another round of public consultation and, finally, the plan is to absorb it into the city development plan.

Many of the submissions to the public consultation had criticised the council for failing to meet national guidelines for density, says the report.

But that was actually a difference in how they had calculated, said the council report.

The Ballyboggan masterplan area cover 77ha. But only 28ha of that is to be developed for housing, the report says.

The April draft masterplan said that build heights of three to four storeys would “be encouraged to provide a coherent street structure, with an appropriate sense of enclosure, while supporting a range of housing typologies and uses”.

That would give capacity for densities in excess of 200 homes per hectare, it says, which aligns with those in the national Sustainable Residential Development and Compact Settlement Guidelines (2024).

It would result in about 6,087 apartments, it said.

The report presented to councillors on the Central Area Committee on Tuesday shows that the post-consultation version of the masterplan shows most of the sites with maximum heights of either up to six storeys or up to eight storeys, it says.

Heights in the four to six storey range “will be encouraged to provide a coherent street structure, with an appropriate sense of enclosure, while supporting a range of housing typologies and uses”, it says.

It gives the same density range of between 100 units per hectare to 250 units per hectares.

Some of the 144 submissions to the public consultation expressed support for the vision in the draft masterplan. Others said it wasn’t ambitious enough, and could be denser.

“A number of suggestions for increasing heights are put forward, with some suggesting increases to 10-20 storeys as appropriate, particularly towards the centre of the site or fronting Tolka Valley Park,” says the new report.

Meanwhile, other residents raised concerns about homes near the new development being overshadowed.

Landowners and businesses now located in the industrial estates were generally supportive of the masterplan, it says, but some said they wouldn’t be able to relocate their businesses.

Multiple landowners and developers petitioned the council to increase the heights allowed on their plots of land.

That does create affordability and viability challenges though, says Reynolds.

Indeed, “of you are allowed to build higher, the land will sell at a higher price,” says Joseph Kilroy, head of Ireland policy and public affairs at the Chartered Institute of Building.

But the homes won’t be cheaper, he said. “Once you need lifts, you increase the price of building dramatically.”

That’s why higher-rise apartment-building is not cheap, he says. Landowners can want to increase heights to increase the value of their land, says Kilroy.

The council has to work with the landowners, he says, because if it doesn’t they could just decide to sit on the land. “At the moment because the state lacks the capacity as a developer, the landowners hold all the cards.”

Reynolds, the architect, says there is a solution. Some existing housing estates in Dublin that he knows have 169 homes per hectare, he says.

To achieve around 200 homes per hectare, consider building maisonettes, he says, or duplex homes above ground-floor apartments.

But if the council allows high-rise, the landowners will seek to maximise their land value by going for planning permission for the tallest possible developments, he says.

The new ministerial guidelines – the rules set by the Minister for Housing that override councils’ provisions – allow for total flexibility on unit mix, says Reynolds.

So high-rise developments are likely to include a lot of one-bedroom homes and studios, which are generally more profitable than larger family homes, he said.

“There shall be no minimum or maximum requirements for apartments with a certain number of bedrooms,” says the new guidelines.

Kilroy says the biggest problem he sees is that the state is rezoning land for homes, which increase the land values by hundreds of percent but without getting in on the action itself.

“It strikes me as a huge missed opportunity,” says Kilroy. “The state should purchase the land ahead of rezoning and take advantage of the uplift to deliver amenities.”

In the United Kingdom, the government has established a state development company to do that, says Kilroy.