Dublin city councillor proposes reducing contacts with US government, given its crimes

Although it’s unclear exactly what the council could do on this front.

As the Repeal the 8th campaign gears up, some grandparents are planning to join the charge. It was, after all, their fight to begin with.

One way to terminate a pregnancy was to jump off the coal bucket. Other means, like gin and a hot bath, weren’t so successful.

But so it went for decades, says Dr Sheila Jones, reclining in her chair at home in Templeogue on a recent Friday.

Now 76 years old, she says she hasn’t given up the struggle for safe and legal access to abortion for Irish women. Others of her generation say the same.

And as the Repeal the 8th campaign gears up, this often-overlooked demographic may play a pivotal role in that charge.

It was, after all, their fight to begin with. As they see it, it’s still theirs today.

“There would be a considerable number of women of my generation who’ve been through all of this nonsense,” says Jones, as she offers a plate of biscuits. “We wouldn’t have changed our attitudes at all.”

For Jones, it all started in the early 1960s. As a trainee doctor working in the Rotunda Hospital, she attended to the women of the North Inner City who, after five or six children, invented ways to prevent another birth.

“The poverty was absolutely dreadful,” she said. “They would do all sorts things to bring on a miscarriage. They just couldn’t face having another baby.”

After a stint working as a GP in Belfast, Jones returned to Dublin in 1976 and worked with the Irish Family Planning Association (IFPA), later becoming a medical director.

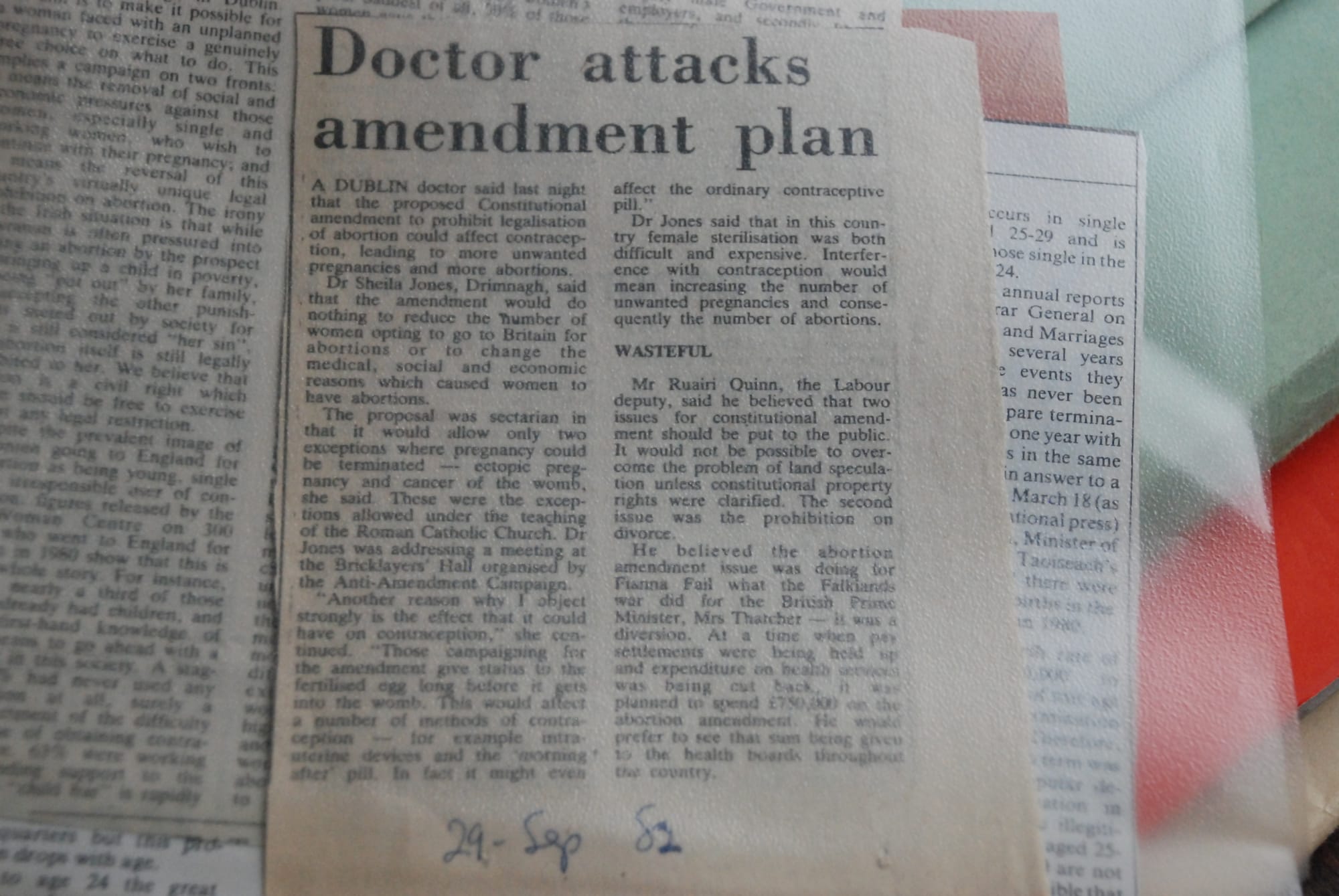

In the corner of her living room, Jones’ 14-year-old dog Sam cleans himself nimbly. On a table by the window is a collection of clippings Jones has saved since her days in the IFPA.

In 1980, she recalls a group of like-minded doctors, herself included, turning their ire towards the recently introduced Health Family Planning Act. The act meant that couples had to get a doctor’s prescription to get condoms.

“Michael Woods was the Minister [for Health] at the time,” she says.

“He refused to see us. But the lads [the male doctors] were all in favour of going to prison, they thought this would be great publicity. I remember thinking, ‘You lot will be alright because you can go to Mountjoy but I’ll be going to Limerick where all the IRA women are.’”

As a lapsed “prod”, as she put it, Jones was reluctant.

Around 1981 and 1982, Jones recalls whispers growing louder.

Ireland was demanding widespread abortion and such murmurings must be quieted, was the message that seemed to come from the conservative side.

Jones recalls it differently, however.

“There was no great urge in the country, at least I didn’t see it, to change the abortion law,” she says. “And then this thing started off about needing a constitutional amendment to ensure abortion never happened in Ireland.”

“I do not remember being on a march demanding abortion,” says Jones. “The first thing I remember was being on a march saying, ‘Don’t put this in the constitution.’ It got so nasty and so horrible.”

With letters to the newspapers defending the rights of the unborn and placards seen in town denouncing abortion and all its evils, Jones says the crozier was thumped in turn and the pulpit bashed.

“It appeared to be that if abortion became available everybody would want one, that we’d all be forced to have an abortion,” she says. “Having worked with women over the years who were going for an abortion, or had abortions, this was so far removed from the truth.”

On the day the amendment was passed, Jones remembers feeling sadness. “Just sadness, and knowing it was going to be a disaster,” she said.

In 1992, there was the notorious X-case, in which the attorney general sought an injunction to prevent a teenage girl, who had been raped, from traveling to the UK for an abortion. That led to a Supreme Court ruling that determined abortion was allowed if a pregnancy posed a risk to a woman’s life, including suicide. It galvanised many people who’d been “left simmering there” since 1983, said Jones.

“They felt bruised at the amendment but here was something that was obviously wrong and needed to be righted,” she says. “But politicians are scared of abortion, it’s a bad subject. This Citizen’s Assembly is one way of putting the issue onto someone else for instance.”

Thirty-three years since the 8th Amendment passed, those in their late seventies, like Jones, find themselves still railing against this “hypocrisy” and what they see as the ignorance of others their age.

“I was at a social thing last week, a group of women sitting chatting, and someone said ‘Isn’t it dreadful, all the abortion here?’” says Jones. “‘Excuse me,’ I said, ‘There’s no abortion here. Where did you get that from?’”

Jones reckons it is imperative to counter such ignorance and has done so with the help of others of the older generation. “Grannies for anti-amendment?” she says, chuckling.

Well, says her friend Bernadette Andrews, why not?

Andrews wears her 79 years with panache. With scones in one hand and coffee in the other, she recounts her disbelief when the amendment passed.

Andrews met Jones in the 1970s, while working in the IFPA, and the two have remained friends socially, and staunch allies where women’s rights are concerned.

“My attitude is let people live their lives. Why should I interfere in someone else’s life?” she says. “I find it very difficult that people are so condemning and judgmental.”

The local postman often delivered stacks of hate mail to the IFPA office on Mountjoy Square, says Jones.

“They would think of us, some people, as being prostitutes for working and handing out contraceptives,” she says. “I thought it was quite exciting and pioneering myself.”

Abortion is ultimately a cross-class issue, says Andrews. Many who could afford an abortion in the 1970s, whether they approved of it or not, had to confront it.

“Well-off and middle-class mothers would bring their 15- and 16-year-old daughters in to go for abortions,” she says. “It was totally against everything they were brought up to think but yet when their 15- or 16-year-old daughter got pregnant they wanted them to go the England.”

Every wall in Andrews’ house is covered with artworks and family pictures, many of which are of her late husband, Fianna Fail TD Niall Andrews.

Does she feel frustrated, like Jones, that politicians continue to stall?

“All politicians are afraid of losing their seat but they should come out and be more open about this,” she says. “They have to take responsibility to govern.”

Raised in a Catholic family in West Cork, Andrews’ work with women in the 1970s solidified her opposition to the current abortion legislation, and she says it’s time her generation showed their opposition more actively.

“This time last year I had a party here with my friends Ciarán and Julia,” says Andrews. “We said, ‘Let’s start a campaign for the over-seventies for abortion!’ Now, a few bottles of wine were drank, but we never did anything about it.”

There is support among the older generation for repealing the 8th, but they’re not always the easiest people to reach, says Linda Kavanagh, spokesperson for Abortion Rights Campaign.

“An awful lot of the older demographic do come up and say, ‘Fair play,’ and, ‘Isn’t it terrible that we’re still campaigning for this?’” she says.

“They are a really important group but they’re often an overlooked demographic.”

Ciarán and Julía Carty have been married since 1962.

Now 79 and 77 years old, respectively, they’ve known Andrews since their daughters went to school together.

Ciarán was raised in the wealthy suburb of Ballsbridge, while, in 1938, Julía was born in Madrid as the Spanish Civil War roared on.

Ciarán, for many years, worked as a journalist and editor, and Julía worked as a translator.

The passage of the 8th Amendment confirmed the pessimism he began to feel in the 1980s about the country, says Ciarán.

“It was very disappointing. You felt like things were going backwards,” he says. “They copper-fastened it into the constitution, which was ridiculous.”

Even after Savita Halappanavar died in 2012 and the government were forced to legislate to protect the life of a woman should the pregnancy endanger her life, they didn’t go far enough, says Julía.

“Fourteen years is what you can get now instead of life imprisonment,” she says. “It’s typical of what happens here. They never do nearly enough and they do it far too late.”

As voters, and citizens, Julía and Ciarán feel that their generation are too often dismissed after retirement.

“It’s very irritating,” says Ciarán. “There are an awful lot of us who would still be what we were in the 1960s, perhaps even more so.”

Ciarán says men of his generation perhaps aren’t as active as they should be on the issue.

“I don’t want to generalise too much because that’s not fair,” he says. “But nowadays there are lot of young men who would turn out for this.”

Jones, like the Cartys, points to last year’s marriage-equality referendum as a game-changer for many, particularly of her generation.

“To change the 8th Amendment it would have be that type of campaign,” she says. “People were talking about their son, or their daughter or their sister. It has to change, it has to become more humanised than last time. The last time was vicious, there was no humanity. It was awful.”

Like Andrews and the Cartys, it goes further than just repealing the 8th for Jones. That, she says, would be just the start.

And like many of her septuagenarian peers, she’d march tomorrow to get it.