Grand vision for Pigeon House on Poolbeg Peninsula is shrunk way down – for now

Council officials want to keep renting it for about the next five years to the wastewater plant operators.

“We remember the work which you believed deeply in, and all of the people who were recipients of your efforts for change, one case at a time.”

A trade union flag bobbed in the air as people clustered around a wooden coffin outside the Church of the Good Shepherd on Nutgrove Avenue, last week.

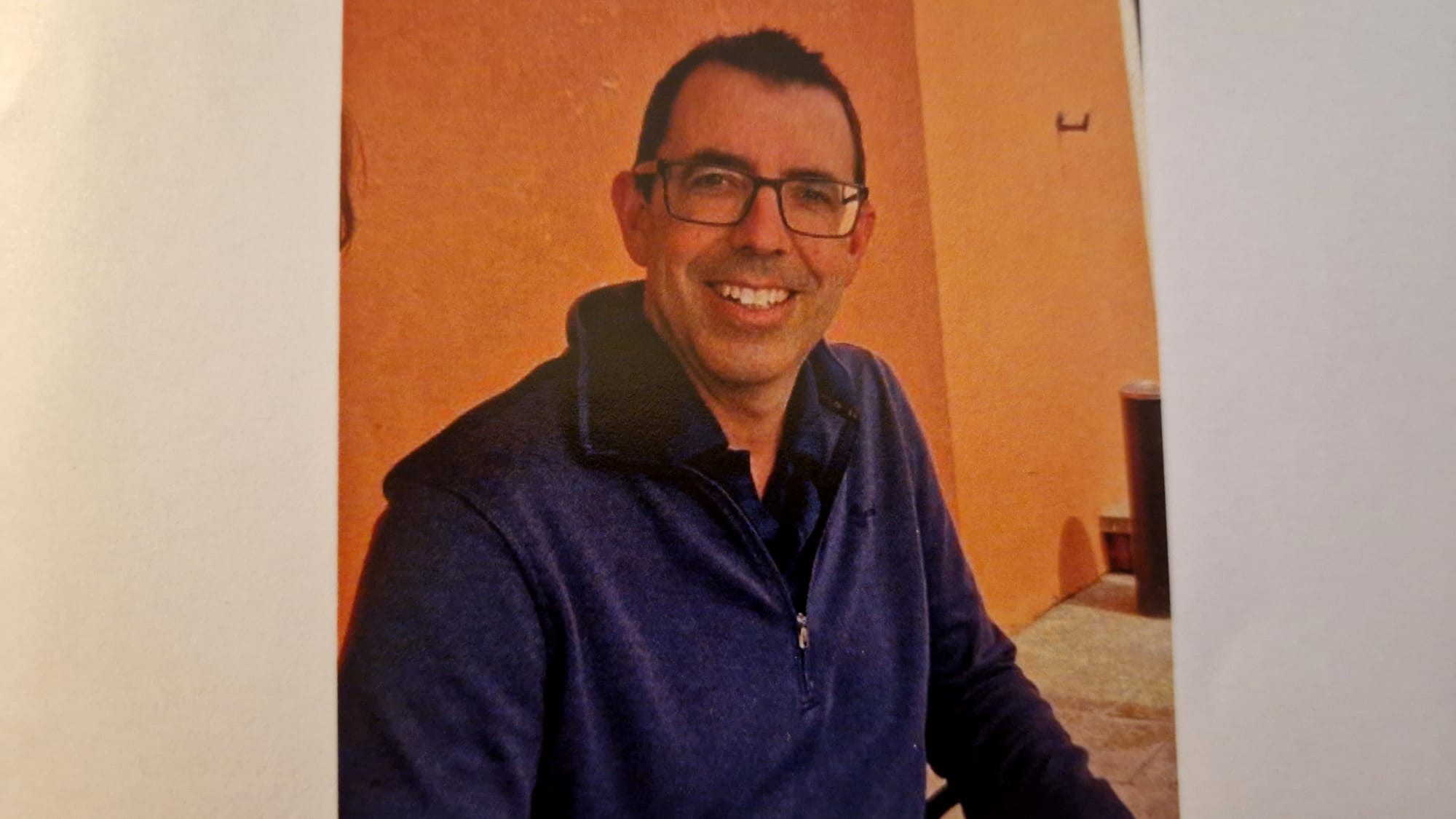

The crowd was letting go of Bill Abom, union man and a social justice campaigner who devoted his life to making immigrant workers feel seen by mobilising them to speak up and unshoulder their pain.

At the Migrant Rights Centre Ireland (MRCI), and during his time with trade union Mandate, Abom worked to bring unruly employers to heel, saying immigrant workers swallow abuse because they’re afraid of getting deported.

He helped conduct surveys to show their struggles were collective, lobbied the government, joined picket lines and protests, and spoke to the press.

But more than anything, “he built the capacity of many migrant workers to stand up for themselves”, said Lucy Peprah Dubin, who worked with Abom at MRCI.

“We remember the work which you believed deeply in,” said Abom’s wife, Fiona, at his funeral mass, “and all of the people who were recipients of your efforts for change, one case at a time.”

William Abom was born in Burlington, New Jersey, in the United States, on 10 February 1972, said his brother John “Jay” Abom.

Shortly after, his family moved to Pennsylvania, where he came of age, graduating from a Doylestown High School in 1986.

He went to college in Georgetown, Washington, D.C, initially with a view to becoming a doctor, earning a bachelor's degree in biology in 1994.

One spring break, while working on a “service project” at an orphanage somewhere on the Jersey shore, he met Fr. Richard Frechette, a Passionist priest/doctor, said his brother Jay.

Watching Fr. Frechette’s devotion to caring for orphaned Haitian kids, he was stirred to later carve out a career in social justice.

“He actually considered very very seriously becoming a priest,” said Jay on a WhatsApp call on Monday.

He didn’t end up doing that, but his faith was always important to him, he said.

After graduation, he taught science and doubled as a soccer coach at a high school in Brooklyn, New York, for a year, said Jay.

Later, he worked in Haiti and then in Guatemala for nonprofits, probing scars of poverty and dreaming up solutions.

In Haiti, he worked at an orphanage. In Guatemala, he helped set one up and learned to speak Spanish, said Jay.

After, Abom moved to Ireland to do a graduate degree in development studies at the Kimmage Development Studies Centre, which was then based at the Holy Ghost Missionary College.

“His areas of interest include community organising, grassroots participation, and effective partnership,” says a short bio at the end of an academic paper he wrote in 2004.

The paper explored the role of community organising and civic participation in weaving long-lasting safety nets, drawing from his work with low-income families in Guatemala.

Abom, who had met his future wife, Fiona, in Haiti, proposed to her in Ireland, at the foot of Mount Errigal, in the Church of the Sacred Heart in Dunlewey, County Donegal, said the priest at his funeral mass.

They moved together to upstate New York, where he helped organise immigrant farm workers for a while at the Rural and Migrant Ministry Inc. (RMM), a faith-driven social justice organisation, before moving back to Ireland for good.

“Bill was the visionary behind establishing RMM’s first March for Farmworkers Justice from Blackport to Albany as he joined with the late Jim Schmidt to walk 245 miles, at times through blizzards,” said a tribute post by the RMM.

When Abom showed up asking about a “drop-in centre coordinator” job at the MRCI in the early aughts, Siobhán O'Donoghue – then its director – thought the role was too small for his vision, she said recently by phone.

“I could see that he was an organiser, he was a community worker, I could see the talent, immediately,” she said.

The centre was barely scraping by at the time because it was new, said O'Donoghue.

“I remember persuading a funder to give me a little bit of money, to kind of, you know, put the tiny bits of money together to give this guy a job,” said O'Donoghue.

She didn’t want to lose him, O'Donoghue said. “I was like, oh my god, if we don’t do this now, somebody else is going to get him,” she said, laughing.

Together, they strategised for a swirl of immigrant-rights campaigns over the years.

“He created conditions for people themselves to be empowered, not doing things for people,” said O'Donoghue.

They set up the Mushroom Workers Support Group as Abom reached and rallied underpaid and overlooked immigrant farm workers again.

An MRCI report dated November 2006 charts contours of isolation, hardship and injustice shouldered by mushroom pickers.

Its foreword is written by Hollywood actor Martin Sheen, who was drawn to the campaign while attending the University of Galway as a mature student.

Anna, a mushroom picker from Latvia, had told MRCI that she’d mixed chemicals to spray on the crop without any safety gear. She has poor eyesight, coughs a lot and gets short of breath, says the report.

“My English is not very good and it is hard to communicate with people [...]. I don’t feel very comfortable around Irish people and I don’t have any friends from my home country to mix with only the two girls who I am sharing house with. Most of time I spend in the house,” she’d said.

O'Donoghue, former director of MRCI, says she remembers Abom driving to Cavan and Monaghan on Sunday evenings to meet those workers – always staying the course.

“Sitting in people’s houses, people would gather around and would talk to him,” she said.

He nudged mushroom pickers to muscle through daunting bureaucracy and lodge exploitation claims.

A photo in the Anglo-Celt newspaper dated 19 January 2006, shows a clutch of women sitting and standing outside the Cavan offices of trade union SIPTU, which was helping them.

Abom had told the newspaper that almost all mushroom pickers in Cavan and Monaghan were immigrant women who had settled for the job because they couldn’t get hired elsewhere.

In other campaigns, he marshalled collective bargaining efforts of immigrant restaurant workers for years. One time dressing up as a chef outside the Dáil in protest of wage cuts.

For decades, he fought for the reform of work permit rules for those whose right to live here depends on them and makes them vulnerable.

Last year, at a conference in Dublin City University (DCU), Abom spoke passionately about building momentum around making the price of Irish Residence Permit (IRP) cards more affordable. At the moment, it’s €300 for most people, paid annually by some.

As Mandate’s lead organiser, he planned industrial actions that won big, said his pal and former colleague in the trade union, Dave Gibney.

His vision for the Decency for Dunnes Workers campaign helped the union to flourish and see an upswing in membership for the first time in many years, he said.

“He helped the union grow 1,500 members or so, maybe more,” said Gibney.

He and Abom stayed alongside workers in the Paris Bakery as they occupied it in a bid to claim unpaid wages, “until there was an agreement” to pay the workers some of the money they were owed.

But Abom told the workers that it’s their voices that matter the most, Gibney said, and that he and others were just union folks who had their backs.

“He used to say the core of community work and the work we do is the three Rs. Relationships, relationships, relationships,” said O'Donoghue, the former director of MRCI.

“And it didn’t matter who you were, he treated everybody the same.”

Abom, who served as MRCI's co-director before his death, continued to attend some work meetings remotely until recently, said Gibney, who now works there.

He was especially keen to join a meeting about family-reunion rights of immigrant workers, Gibney said.

And he was worried about the rise of xenophobic hate, he said, thinking up solutions, as he always did.

Though he figured largely in the success of their union crusades, he didn’t seek personal attention or try to grow his profile, Gibney said.

Bill Abom was an outdoorsy, athletic guy who excelled at golf, but the way he lived his life smashed stereotypes about golf players, the priest joked at his funeral mass.

He said the rich should give back. “They have not yet been called upon to do enough for the common good of the country,” he told the Wicklow People newspaper in 2011.

As a dad to three kids – Liam, Thomas and Anna – he blasted “Eye of the Tiger” some mornings to wake them up for gym.

And if they wouldn’t budge, he would tease them, saying, “Get out of bed, you lazy maggot,” said one of his sons at the funeral, putting on his dad’s American accent.

He and his mum loved each other in the warm, unwavering way that makes kids look forward to being at home, his son said.

He could fix every broken tool, and liked to brag about how much buying a new one would’ve cost them, said his daughter Anna.

“He was so good at everything,” she said.

Abom died at home on 30 November after three years of living with cancer. He was 53.