Tusla says it's an offence to run an unregistered children’s home, but it places children in them anyways

So how does it square the circle?

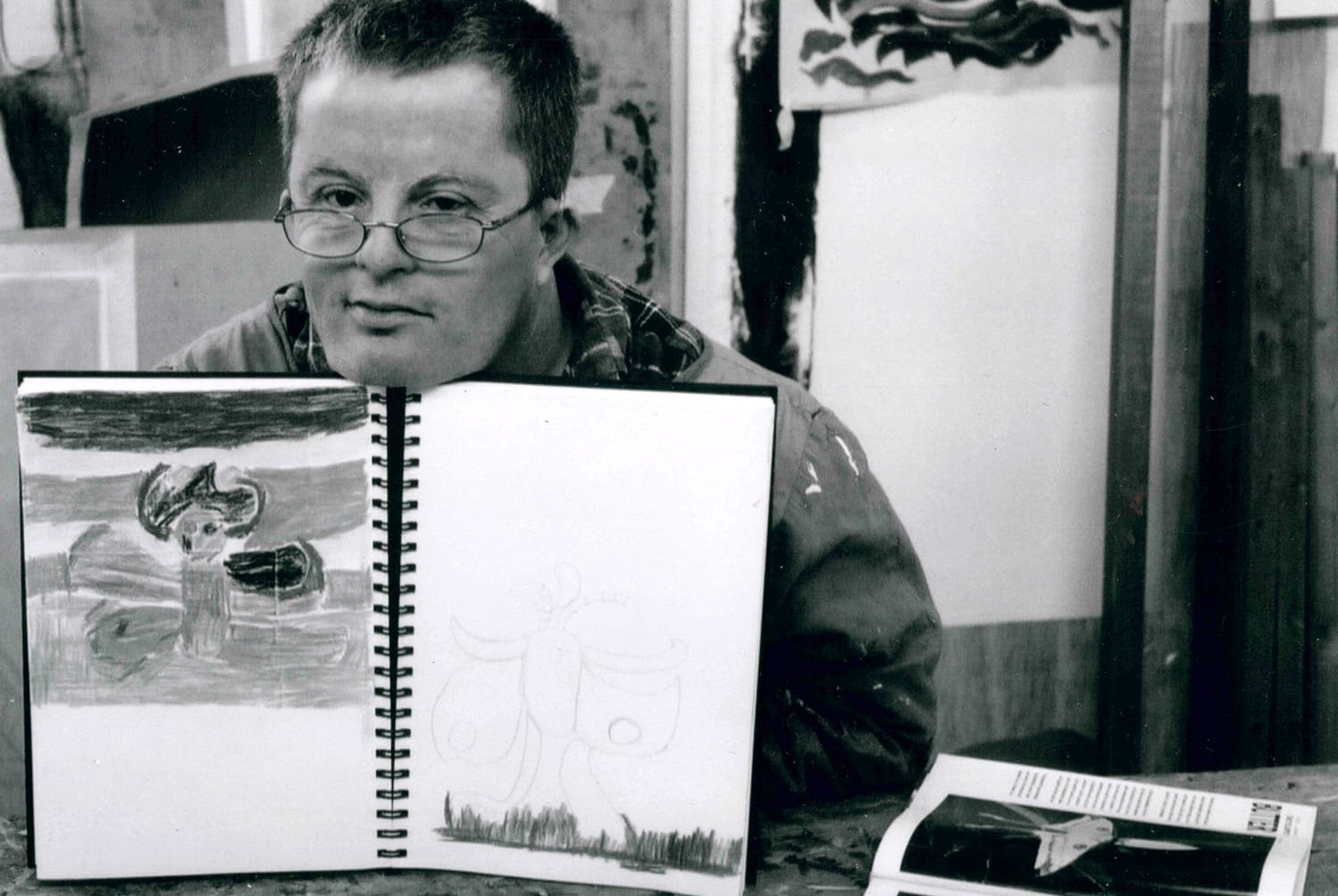

The sculpted relief was created in the ‘90s by Georgie McCutcheon, a painter, sculptor and activist in the field of disability and the arts.

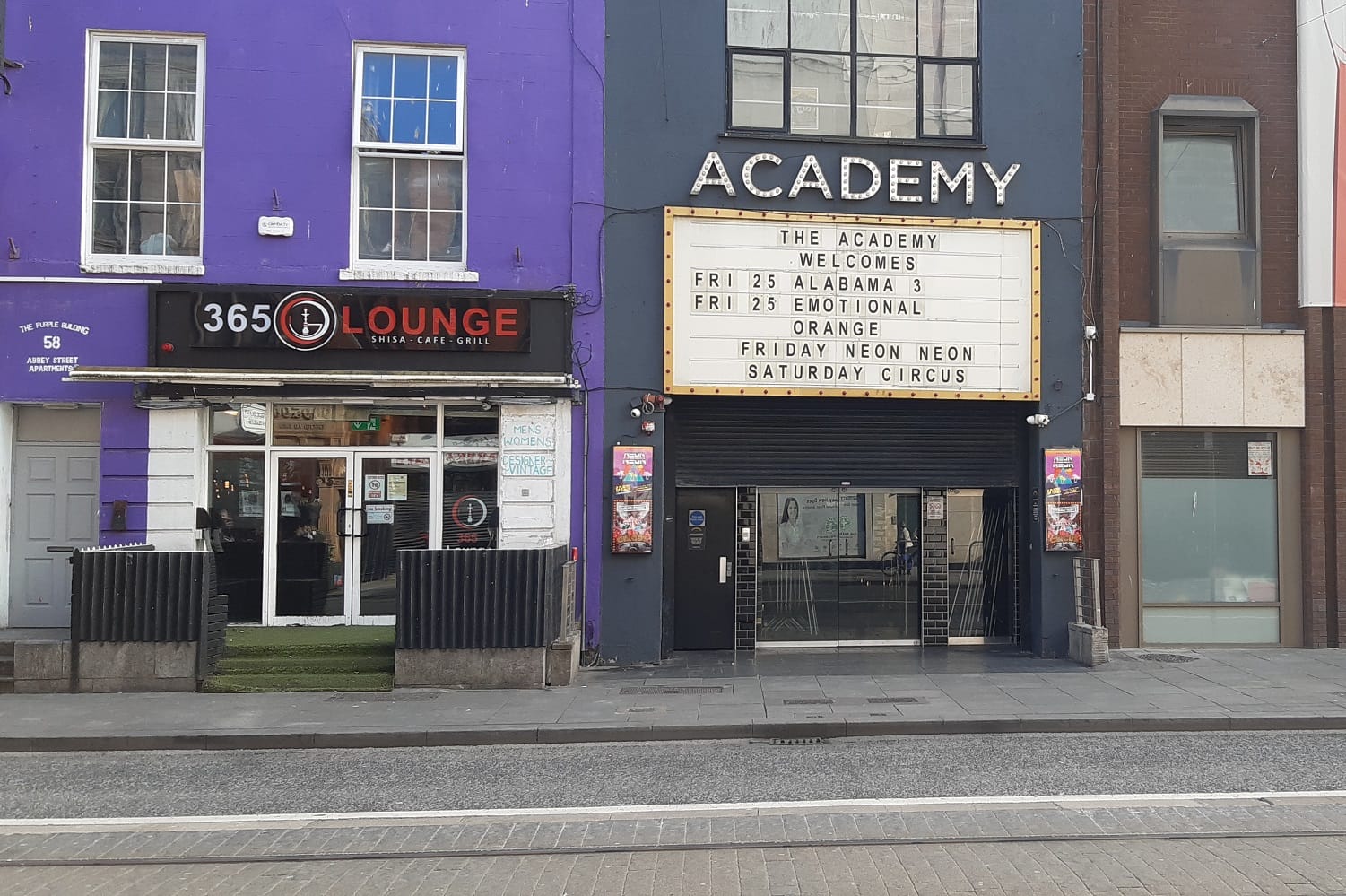

In the evening, the lights switch on behind the retro marquee sign that hangs down over the entrance to The Academy venue on Middle Abbey Street.

These days, the garish white board announces upcoming live events.

During the pandemic, it hosted comments on the latest trending stories, quips that imitated the tweets of an alienated Dubliner, and, invariably, spread fast over timelines.

Before this sign was erected, the face of the building was defined by a less ostentatious display. For years, its chief marker was a sculpted relief.

The work, which predates The Academy and today is mostly hidden behind the sign and a shutter, is a series of circular images etched into limestone panels above the front doors.

Each panel depicts either an instrument or a smiling musician. One is performing on a fiddle, another is beating a bodhran.

The figures are composed of thick lines, with round bodies and misshapen limbs. Their forms aren’t realistic, but simplistic and surreal.

From the street, just a single character is glimpsable, that of a flautist. Her arms protrude from her hips and quavers float into the air.

What she is doing, however, won’t be obvious to most passers-by. The shutter, even when rolled up, obscures most of her body.

But ticket-holders who glance up in the brief moment that they exit the queue and enter the reception, may catch her and the other figures playing away.

Created in the late 90s, the original relief was once twice as big, spanning almost half of the main façade.

When the venue was bought by its current owners, Shine Production, the lower portion was replaced by generic tiles, including the bit bearing the artist’s name: Georgie McCutcheon.

A painter, sculptor and activist in the field of disability and the arts, McCutcheon was born in 1958 to parents who were members of the farming gentry in Tipperary.

He was born with Down’s syndrome and, before the age of one, McCutcheon was sent to Sunbeam House, which was at the time an orphanage and home for children with intellectual disabilities in Bray.

“He never knew his family,” says Gladys Lydon, a lifelong friend and co-founder of Camphill Ballytobin, an intentional community for people with disabilities in Kilkenny.

“He was a very deprived person. You got to know that when you got to know him. He was outgoing, talkative and confident,” she says, “but he had a vulnerable side.”

In his early teens, McCutcheon often travelled to Wexford, spending his summer holiday with friends living in Camphill Duffcarrig, a similar community outside Gorey.

There, he befriended a voluntary worker, Patrick Lydon, the late husband of Gladys.

Patrick Lydon was from Massachusetts and had left the United States as a conscientious objector to the war in Vietnam. He joined Duffcarrig in 1972.

Lydon passed away in January this year. But six months before his death, he talked about meeting McCutcheon for the first time. He was, said Lydon, “a ball of energy, full of mischief.”

“He was feisty,” Lydon said with a laugh. “I liked that kind of thing.”

When McCutcheon moved to Duffcarrig, Patrick had already left to work at a Camphill community in Aberdeen.

Then in 1979, once Patrick returned to Ireland with Gladys to set up Ballytobin, he crossed paths with the artist again. McCutcheon eventually went to live with the couple in 1982.

“We had always a plan in Ballytobin that it was a place for children,” says Gladys. “But some adults would live with us as helpers and Georgie came as a helper. He was a great gift.”

Each day, Gladys says, McCutcheon helped her to make lunch for 24 of the community’s residents. He looked after her young children, answered phone calls and, in his downtime, practiced his art.

“He had a phase of drawing on slates,” says Gladys, “and got into cardboard, three dimensional pieces held together by Sellotape.”

Often, he created sculptures as gifts for specific occasions, she says. At one point, he built a miniature slide for Gladys’ daughter’s guinea pig.

Crosses were a recurring motif in McCutcheon’s work, she says. “They nearly always had a religious theme. Three crosses.”

Another recurring image was the sun, says Paul Bokslag, a painter based in Kilkenny.

The power of the sun was really connected to McCutcheon’s work, he says. “It’s warmth and nourishment. Sometimes he’d put a face on it. He had a really particular visual vocabulary.”

McCutcheon drew influence from the Spanish painter Joan Miró, whose hard-to-classify work explored the subconscious through bold and vivid colours and abstract figures.

By the late-80s, as McCutcheon honed his own style, Patrick sought to find him a mentor, says Gladys. Patrick roped in local artists to teach him life drawing, mosaic assemblage and concrete casting.

“He was very prolific and never stopped working,” says David Lambert, his stone-carving mentor.

Lambert brought McCutcheon to his workshop, he says. It was there that, together, they made the Middle Abbey Street relief.

McCutcheon painted the images, which Lambert, his apprentices and McCutcheon chiselled and sandblasted onto limestone.

It took a couple of years, Lambert says. The pair also made a sculpted high cross for a theatre in the Ballytobin community.

In 1999, McCutcheon’s relief was unveiled as part of the Hot Press Irish Music Hall of Fame, a memorabilia museum of Ireland’s musical history.

Lambert and McCutcheon went to Dublin for the event, says Lambert. “The drummer from The Corrs had her hand cast in concrete. Georgie always rose to these kinds of occasions. At openings, he’d talk endlessly about what he was doing.”

The Hall of Fame closed in late 2001 and was replaced by Spirit nightclub.

In 2007, The Academy opened in its place. Until 2014, McCutcheon’s relief was fully visible, though the surface had whitened with efflorescence.

Then, in September 2014, management at The Academy changed. According to a press statement, the venue was refurbished in a “Victorian music-hall style”. During this process, six of the limestone panels were removed, including those containing a fiddler, dancers and a saxophonist beside McCutcheon’s signature.

The Academy hasn’t responded to queries as to where the panels went.

Bokslag and Lambert assume they were lost or destroyed, they say – but are sanguine about that.

“With anything in the public domain I’m involved in, I tend to let it go,” says Lambert.

“I did a carving for Collins Barracks, for the monument there, and a couple of years later, I went back to see it and it was totally vandalised,” he says. “I let things go.”

In the latter half of his life, McCutcheon relocated to Callan, a town neighbouring Ballytobin, Bokslag says.

There, Bokslag says, he helped Patrick, Gladys and other Camphill associates to found the Kilkenny Collective for Arts and Talent, an inclusive arts centre for people of all abilities.

When the KCAT Art and Study Centre opened in 1999, McCutcheon was christened its “father” – around the same time that he started to refer to himself as Lydon-McCutcheon.

His works were exhibited in Germany, the Netherlands, Sweden and in the United States, according to KCAT’s website. His show in the US was at Patrick Lydon’s alma mater, the Phillips Exeter Academy in New Hampshire, Bokslag has said.

In 2014, McCutcheon was given a retrospective in KCAT, and according to Gladys, two of his biological brothers visited the show.

“I said to one of his brothers, ‘It would be great to meet and tell you about Georgie, because he’s had a great life,’” says Gladys. “But they chose not to meet him. Both saw him at a distance and bought a lot of his work.”

Gladys says one brother told her that they had memories of McCutcheon as a baby and that after he was brought away, he was not spoken about in the house.

“The family circumstance was very sad,” she says. “But it was the times. It was something that shouldn’t be judged.”

McCutcheon was diagnosed with dementia, and he passed away in October 2015, at age 57.

“I think he would have died of dementia years before, if he hadn’t been an artist,” Gladys says. “It was incredible how he was driven to do art every day in the last 15 years.”

McCutcheon was a legend, says Pádraig Naughton, director of Arts and Disability Ireland. “He led the way for a generation of artists.”

He was the inspiration and the driving force behind what is KCAT today, says Naughton. “And he was an incredible spokesperson and representative for KCAT, which has been very difficult to replace.”

According to Bokslag, one of Patrick Lydon’s final statements in the days before his own death “was that he was looking forward to meeting Georgie again”.

Bokslag still misses McCutcheon, he says. “He was such an inspiring, living person. People responded to that.”