Skeletal remains found during construction at Victorian Fruit and Vegetable Market

The bones are thought to come from the major medieval monastery at St Mary’s Abbey, and further excavation works are ongoing.

Residents continue to differ with the Hines not just about key characteristics of its scheme on the site of the old Player Wills factory, but also about whether the community consultation is actually real consultation.

“Our door is open, the more engagement we have the more positive benefits we can explain,” said Gary Corrigan, managing director of real estate firm Hines, speaking on a Zoom call last Thursday.

Hines staff presented to the public plans for developing lands around the former Player Wills factory in Dublin 8 which, if permission is granted, would include 331 co-living units, 466 build-to-rent apartments and a childcare facility.

Those plans are phase 3 of a larger masterplan for the area, which aims to deliver around 1,400 new homes across the Hines-owned land and another 600 or so on adjoining council-owned land at St Teresa’s Gardens.

A small park, a destination playground and a full-size sports pitch are included too. The complex would scale new heights for the Dublin 8 area, reaching 22 storeys.

Hines has organised several community events around its plans for the neighbourhood.

But some residents continue to differ with the developer not just about key characteristics of the scheme, but also about whether that community consultation is actually real consultation.

A spokesperson for Hines says that it has changed aspects of its plans due to feedback received from residents’ groups.

“Consultation and engagement may or may not bring about a change in design,” says the Hines spokesperson.

“Some changes may not be commercially viable for Hines or commensurate with best practice residential and regeneration area design,” they said.

Joe Clarke, a spokesperson for the Dublin 8 Residents Association, says that one of the main problems is that when Hines originally announced its plans in 2019, it said the development would be a mix of rental and for-purchase homes.

Shortly before a first open day in July 2019, Hines sent a draft frequently asked questions (FAQs) document to Dublin City Council, attached to an email.

In the email, Hines’ marketing manager said: “We have also compiled a list of questions which may be asked by members of the public regarding the development.”

It asked the council to review them and let them know if they had any comment on the answers – and suggested Dublin City Council compile a similar list “in case you are asked any questions by the public over the 2 days”.

Among the questions was “Will any of the apartment units be offered for sale?” with the draft answer saying: “It is envisioned that the scheme will include a mixture of homes both for rent and for sale.”

That draft list of FAQs was released by Dublin City Council under the Freedom of Information Act, but the spokesperson for Hines said that it was not an approved document.

“There was no suggestion in our 2019 Boards to suggest that units would be for sale,” says the Hines spokesperson. “That is not something we indicated in any publicity information or media releases.”

At the time, it was reported in the Irish Times and in Dublin Inquirer.

And in a recorded interview at the July 2019 open day, Andrew Nally, an analyst with Hines, said that while most of the homes would be rented out there would also be homes for sale in the development.

“No they won’t be all build-to-rent,” he said. “It isn’t decided yet what that portion will be but there will be a portion of the houses that will be built to sell.”

Another key point of contention is height. The masterplan shows buildings rising to 22 storeys on council land and 19 storeys on Hines’ land.

What the spokesperson for Hines says residents were told about heights and when, and what panels from the 2019 open-day show, seem to differ.

The spokesperson for Hines says that their open-day display in 2019 clearly showed their intention to build more than 15 storeys on the site.

“Design studies are currently underway … and are likely to include some signature elements and a number of floors above the 15 storey level,” their display boards read, according to the spokesperson.

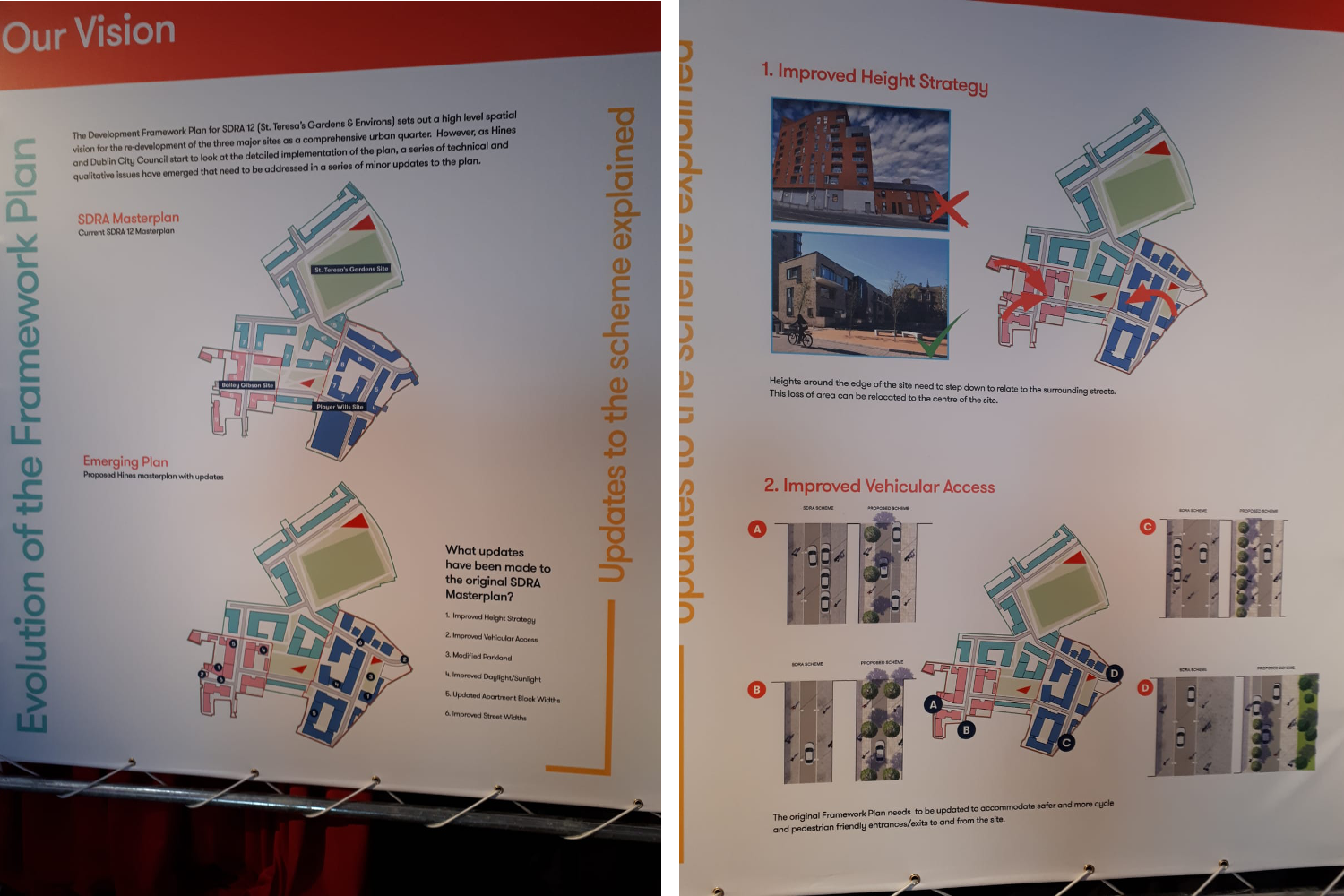

Images of two panels from the 2019 open-day that mention heights, though, simply say that the masterplan had an “improved height strategy”, and that the “Heights around the edge of the site need to step down to relate to the surrounding streets. This loss of area can be relocated to the centre of the site.”

It’s possible that text on another panel was different, but none of the other images of panels taken on the day by a reporter have any more detail on heights.

An image from the March 2020 open-day, which was sent by the spokesperson for Hines, does say that its intention is to go above 15 storeys.

Residents saw immediately that the buildings would be totally out of character with the area, says Clarke. “We all looked at it and said ‘Oh my God, the scale of it.’”

Locals expected that An Bord Pleanála would take into account their observations and the character of the area, he says.

Clarke says he actually thought that the developer was only “kite flying” when it suggested building 19 storeys. He thought they were leaving room to compromise, he says.

But An Bord Pleanála granted Hines permission for the first phase.

At the recent public meeting on Zoom, Kieran Mulvey chaired. He hurried Hines staff along on the presentation so he could get to the questions sent in people by chat.

Residents wanted to know what the rents would be.

Brian Moran, senior managing director with Hines, said that the rents will be “generally in line with market rents”.

“As things stand we have a viable scheme,” he says, but if rents were to drop they might not.

Residents wanted guarantees that all of the communal space promised in the plans would be fully open to the public.

The entire complex and all its courtyards would be open for people to be able to walk through it. It is “100 percent open access”, said Gary Corrigan, managing director of Hines.

Ryan Crossman, development director at Hines, said that they were building the park, pitch and playground but that Dublin City Council would take them in charge and manage the facilities.

Clarke says Hines is providing information on its plans through its open days but that it isn’t taking residents’ views into account in its decision-making processes.

Every major change has gone against what local residents wanted, he says.

Most locals want the site developed and were happy with a previous masterplan for the area, which had been agreed by the councillors in 2017, he says. “Why has a private developer been allowed to write a masterplan for an area?”

The spokesperson for Hines says they have made changes to their plans as a result of the community engagement.

After talking to the community representatives and councillors they agreed to retain the whole of the Player Wills factory building instead of just preserving the front bays on the facade, he says.

We “went back to the drawing board to decide on a brand new plan that would allow us retain and reimagine the old building”, says the Hines spokesperson.

Regeneration of urban lands is hugely important and complex and is a common challenge in lots of European cities, he said.

The process for design and delivery is guided by strategic planning and is highly regulated. “It involves many, sometimes conflicting constraints and parameters,” he says.

A wide range of stakeholders including technical experts, public officials and locals contribute to the process, he said.

Hines is guided by the national planning framework, city development plans and local authority guidelines, he says.

A spokesperson for the Department of Housing says all community consultation is optional.

“Community consultation involves project promoters engaging with communities with a view to hearing any concerns they might have in advance of lodging a planning application, so that they might be factored into the finalisation of the planning proposal,” he says.

It is usually for large infrastructure projects and often includes placing advertisements in newspapers putting up a website for the plans, or arranging presentations and listening to the views of attendees.

“While community engagement is not mandatory, it is regarded as advisory and best practice for these types of projects in order to hear community concerns and generate community support,” he says.

There is also a five-week formal public-consultation period within the planning process, where any party can make observations on the plans, he says.

In a Strategic Housing Development, the plans go straight to An Bord Pleanála, so if locals don’t agree with the planning decision, there is no appeals mechanism other than going to court.

That is unfair, says Clarke, because a developer has far more resources at its disposal than a residents’ group.

The Dublin 8 Residents Association intend to fight the plans every step of the way, he says.

“We now have a monster community meeting scheduled,” he says. “Focused on next steps, including fundraising and preparation for the judicial review.”