Who will sit on the advisory board set to shape the future of Dublin city centre?

Seven areas of expertise should be represented, said a recent council report.

Can more be done to bring down cost-rental rents in Dublin?

Brendan O’Connor was resting his elbows on the brick wall around his front yard on Montpelier Gardens.

He was looking out over the road, and up into the sky, at the yellow cranes and scaffolded blocks where new homes are rising up at what used to be called O’Devaney Gardens.

He grew up in a flat in the old apartments, he says, pointing at a higher floor of a new skeletal tower. “I lived about there.”

Once built out, the new development of Montpelier is set to be a mix of social homes, “affordable purchase”, cost-rental homes, and private market.

O’Connor is surprised that two-bed cost-rentals – at least, those cost-rentals due to be finished next year and owned by Tuath Housing – are to have rents set at €1,695/month, he says.

They’re a rental. He thought it would be higher, he says.

Two-bed apartments and houses in the area are much more these days, he says. His daughter is paying upwards of €1,800 a month.

Still, though, it was council land, he says, musing it all over, and it is costly. “Affordable rental at €1,600 a month. Where are they getting those figures?”

That rent is similar to other recent Dublin schemes of cost-rentals, the model of homes where the rents are set based on the costs of construction, finance, management and maintenance.

The Land Development Agency (LDA) is charging €1,635 a month for a two-bed in Belmayne. Clúid Housing is charging €1,625 for a two-bed in Stoneview in Walkinstown.

But it is much more than in some other jurisdictions.

In February this year, about 1,000 miles east of Stoneybatter, in the Hirschstetten neighbourhood in Vienna in Austria – where average full-time salaries are similar to Ireland – tenants rolled suitcases into their new two-bed cost-rental apartments, launched at €681 a month.

Why are cost-rental homes in Dublin so much more expensive? Providers of cost-rental housing in Ireland say comparing across jurisdictions is hard, as the same terminology can conceal significant differences in detail.

“Comparisons from one country to another generally do not compare like with like in relation to housing standards, targeted population, cost details,” said a spokesperson for the LDA.

But there’s another reason comparisons are hard. There is much less transparency in Ireland than in Austria as to the breakdown of delivery costs for real cost-rental projects, and how those feed into the rents.

Rents will come down over time and are lower than market rents, say cost-rental providers. But – given desperation in the rental market in Dublin and a cohort priced out – could more be done to bring them down now?

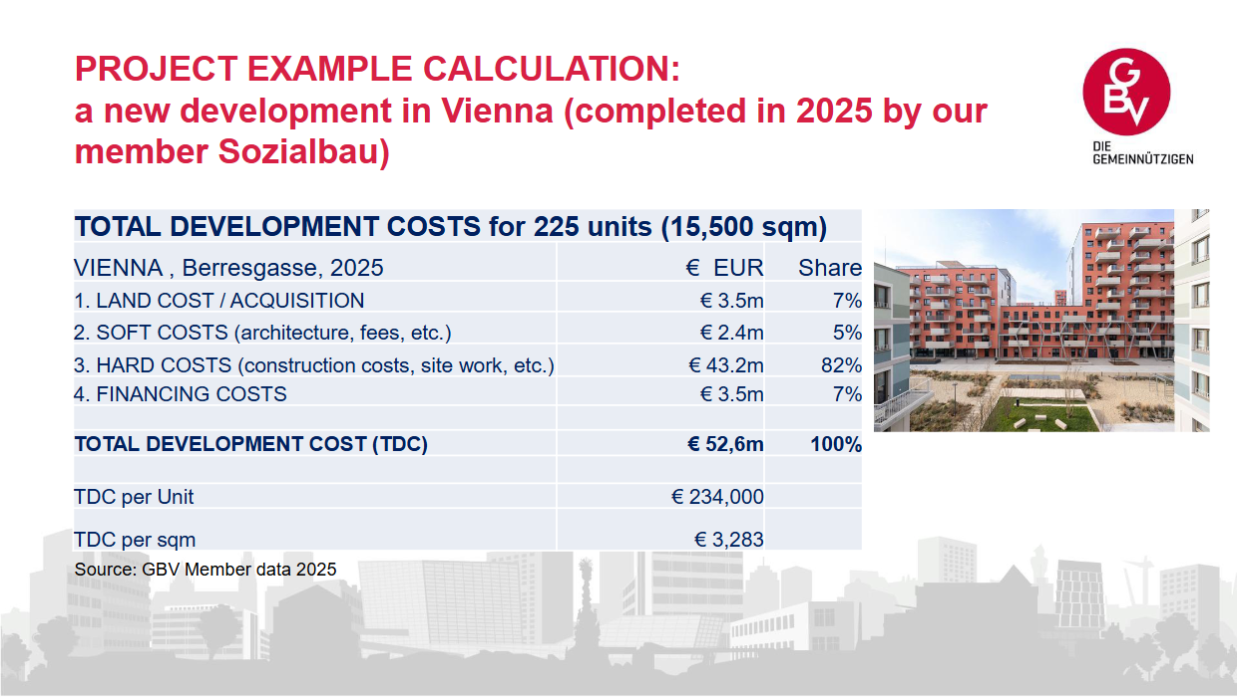

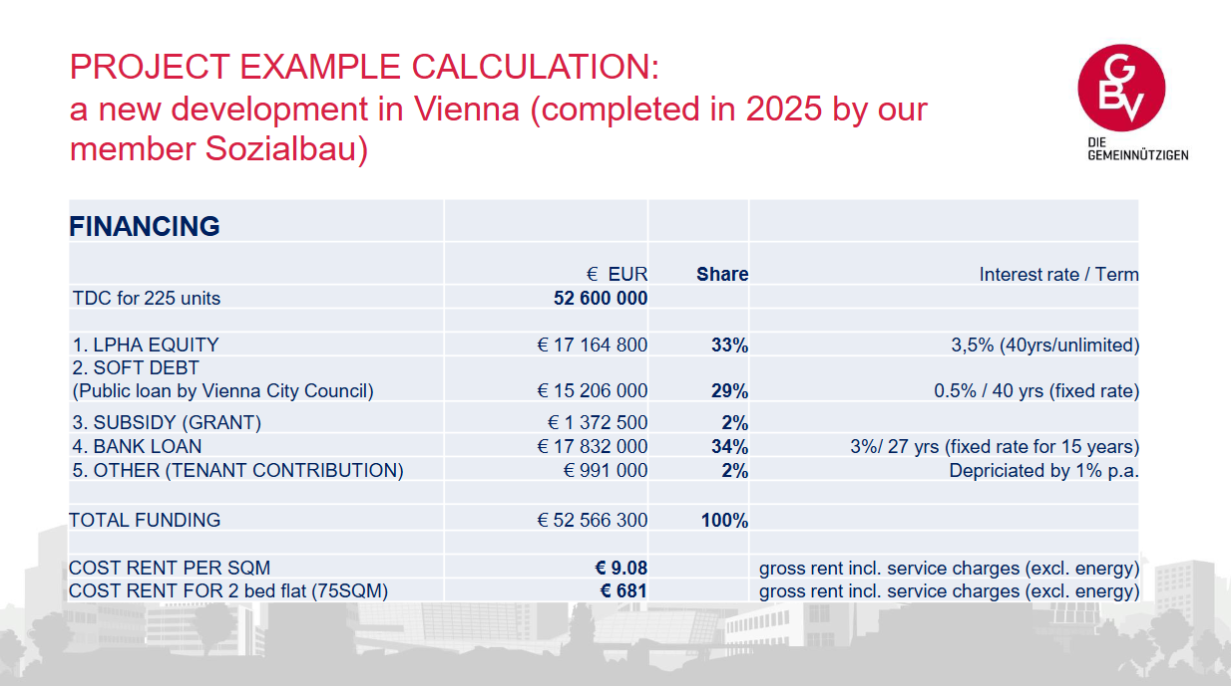

At an online talk in April, Gerald Koessl, a sociologist and researcher at the Austrian Federation of Limited-Profit Housing Associations, gave a breakdown of costs for that Hirschstetten project in Vienna.

He showed how the rent collected covered those costs.

Details of the Hirschstetten project from Gerald Koessl's presentation.

Here, comparable data isn’t public. Neither the LDA, nor Respond, Tuath, or Cluid said they could give breakdowns for specific projects.

But one immediate – and big – difference that feeds into the rent is how much cost-rental landlords collect to cover the management and maintenance fees, and future “sinking” funds.

In Austria, housing associations can charge 55 cent per sqm a month for new-builds, for the first 30 years, to cover the maintenance, says Koessl. For a 75sqm apartment, that shakes out at €41.25 a month. (After 30 years, when the complex is older, it goes up to more than €2/sqm.)

Here in Ireland, approved housing bodies (AHBs) said they couldn’t give a breakdown of how much of the rent they now charge, on average, is for management and maintenance.

But at Woodside, a cost-rental development on Enniskerry Road in Stepaside – delivered by Respond, Tuath, the local council, and the Housing Agency – it was close to 40 percent of the €1,200 a month for a two-bed apartment.

That’s €450 a month.

Eoin Ó Broin, the Sinn Fein TD and housing spokesperson, says he understands the AHBs currently charge between 20 percent and 30 percent of the rent for management, maintenance, and sinking fund.

The LDA charges higher. Forty percent of its rents are to cover management and maintenance, said Ó Broin, the Sinn Fein TD and housing spokesperson, in the Dáil in October last year.

“That’s a big wedge,” he says. “That’s just a decision they have taken.”

That would mean that at Parkside in Belmayne – where the LDA has outsourced the building management – roughly €650 of the €1,635 a month rent for a two-bed cost-rental would be collected for management, maintenance and sinking fund.

A spokesperson for the LDA didn’t directly address queries as to why management and maintenance costs are significantly higher in Dublin, and whether they should be prescribed, as in Vienna.

James O’Halloran, the head of new business at Clúid Housing, said he couldn’t say what the average maintenance charge would be for its cost-rental projects because it varies.

Houses are cheaper to maintain than apartments and facilities can differ, said O’Halloran. “It’s all scheme specific.”

But cost-rental homes are financed over 40 years and designated as cost-rentals for 50 years, he said. “I’ve got to make sure I manage it and maintain it, not just for this tenant, but for future tenants.”

But isn’t that the same for Vienna? That’s true, he says. “And we’re currently working with our operations team that do our forecasts in terms of asset management for the lifecycle of a scheme.”

“We’re constantly challenging ourselves in the organisation to make sure we can provide a great service to our tenants, but an affordable service that the business can operate,” he says.

Mick Byrne, a lecturer in political economy at the School of Social Policy, Social Work and Social Justice at UCD, sounds a note of caution around an easy comparison of Vienna and Dublin.

“As a researcher, it’s easy for estimates for different countries to reflect different things,” he says.

He wonders for example, he said, how much Austria benefits from economies of scale given cost rental is such a large sector. “And with so much of Vienna being cost-rental housing, maybe it’s geographically concentrated.”

O’Halloran, at Clúid, says the models and calculations in Ireland are likely to continue to evolve.

Especially if cost-rental is affirmed as a home for life, if it is thought of more as a social home, rather than a product or a private rental with a more secure lease.

Tenants may bear different responsibilities. And not just for putting in white goods themselves – as they do in Vienna – but also for more maintenance, for appliances that break, he says.

The white walls and empty rooms in the Hirschstetten project do contrast with the elaborate high-specifications finishes and appliances listed in Tuath Housing’s brochure for the Montpelier scheme.

“If you can reduce your input costs at the start, and tenants take more responsibility. That might require a different conversation and a different finance model,” said O’Halloran.

In Austria, “most maintenance and repairs are done by the housing association,” said Koessl, the researcher at the Austrian Federation of Limited-Profit Housing Association.“That would include shower, windows, plumbing, issues with electricity.”

But, “as most flats come unfurnished, a housing association isn’t dealing with any issues related to furniture. This would need to be done by tenants,” he said.

Ireland’s new cost-rental model differs from the Vienna Model in a number of key respects that make it more expensive to provide here, said a spokesperson for Tuath Housing.

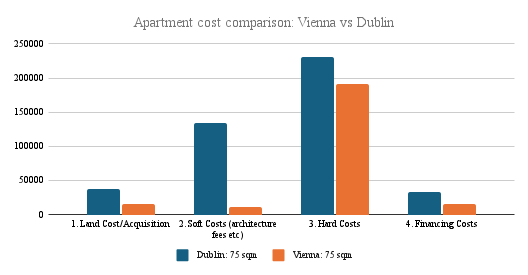

Indeed, the total development cost for that Vienna project was €3,283 per square metre, they said. While Department of Housing figures put the equivalent figure here at €6,502 per square metre, they pointed out.

Comparing a breakdown of those department figures – adjusted for size – and the Vienna project may offer some clues as to where costs diverge.

The department figures are for private development – but many of the cost rentals delivered so far in Ireland have been turnkey homes, new builds bought by AHBs or the LDA from private developers.

The largest difference, that comparison suggests, creeps in through the “soft costs” – with those coming in at €10,700 for a 75sqm apartment in the Austria scheme and at €134,000 for a same-size suburban apartment in Dublin.

Soft costs are the indirect costs – on top of the price of the bricks and mortar.

In Ireland, for two-bed suburban apartments delivered by private developers, department figures put the biggest chunks of soft costs as: VAT on professional fees and construction, professional fees, and developer’s risk/margin.

For the scheme in Austria, only VAT for any non-residential construction in a scheme is passed through to the cost-rents, said Koessl, as VAT for residential construction is deductible. Although, at the end, a VAT rate of 10 rent is applicable to the rents.

Meanwhile the professional fees – those for architects and engineers – are much higher, in the Irish government’s breakdown of total development costs, than in the Vienna scheme.

That could be a difference in whether work is contracted out or done in-house, says Koessl. “I think it has to do with services provided in-house by housing associations.”

In Austria, housing associations are the developers and have significant in-house expertise, so they avoid many outsourcing fees, he said.

Finally, when AHBs in Ireland buy ready-built homes from private developers, or “turnkeys”, they are paying the developer’s margin or profit.

Housing associations in Vienna can include a risk margin – equivalent to a developer’s margin or profit – too, says Koessl.

“But once the building is completed any costs, risk that have not realised are paid back to tenants,” he said. In other words, the rent is lowered.

Depending on the arrangement, AHBs in Ireland may also be covering the full cost of the higher-interest loans – or “developer’s finance” – that the private developer has relied on to build the project.

Many of these costs would stem from how AHBs, in the main, have not been building and delivering cost-rental homes – as the Austrian housing associations do – but buying apartments from private developers and making them cost-rentals.

This is a massive failing, says Ó Broin, the Sinn Féin housing spokesperson.

The Land Development Agency has done it through Project Tosaigh and the AHBs have done it through the Cost Rental Equity Loan scheme, he says.

“That means they’re paying full market price,” he says. “Which includes the private market price for land, developer’s margin, developer’s finance costs. So we’re buying very expensive units.”

“As opposed to large-scale delivery on public land where there isn’t the same land values, there’s no private developer’s margin, the cost of finance is lower because it’s state finance,” he says.

Development finance is a bit cheaper if the developer has a development agreement with an approved housing body, he says. “But it is still private development finance.”

“We’re paying full market price for all aspects of the development,” he says.

Not all of the cost-rental homes being delivered in Ireland are being bought directly from the private market though.

Last week, South Dublin County Council launched Innovation Quarter, the first council-funded cost-rental project in the country.

It cost about €57 million – funded with a loan from the council’s own reserves and a €19.5 million grant from central government, according to a council statement.

The project, which has 133 homes, a mix of apartments and houses, was delivered under a “design and build contract”, with Coady Architects overseeing construction by JJ Rhatigan.

The rents, it has said in a press statement, will range from €950 to €1,550 a month.

The council press office didn’t respond to several queries asking for more of a breakdown of how the rents had been calculated, and the rate of the loan from its own reserves.

They also didn’t respond to a request to talk to anybody about what had been learnt during the project about cost-rental development.

Ó Broin, the Sinn Féin spokesperson, said that his understanding is that the construction costs still shook out higher than officials and councillors had hoped. So they hadn’t dampened rents as much as they thought, he said.

Meanwhile, O’Halloran, the head of new business at Clúid Housing, said his approved housing body doesn’t just buy from private developers. It also has direct-build projects in the pipeline, he said.

Direct builds of cost-rental homes should bring savings, O’Halloran said. “You probably are saving on finance costs.”

Although they also do development agreements, and forward-funding agreements with private developers, to lower or eliminate development finance costs, he says.

“You’d hope that if we provide something with a cheaper rate then the return on the other side should be a lower figure. But that’s project-specific obviously,” he said.

In any case, with direct build, there should also be a saving on margin, he says. “An approved housing body doesn’t need to make a profit, unlike a developer.”

But building homes instead of buying them also brings risk. You have to go through planning, ensure you have a capable contractor, and have access to serviced land, he says.

As he sees it, both “turnkey” models and direct builds need to be looked at in parallel. “The market has a product that can be delivered. That should be looked at if it’s the right scheme in the right location,” he said.

“I think if we put all our eggs into one basket and just do direct build, there’ll be a big gap or shortfall of stuff,” he says. “We’re happy doing both.”

A spokesperson for the LDA said that, as well as fund developments through Project Tosaigh, which means buying from the private market, it does also directly develop cost-rental housing on the land that it owns.

And it’s moving more in that direction, he said. “The latter will become the main delivery method as the LDA’s pipeline advances and more direct delivery projects are completed.”

Still, though, the kind of beast that the LDA is means that it currently has to operate in a way that pushes up its rents, says Ó Broin, the Sinn Féin TD.

The LDA has to pay corporation tax at 25 percent of profit, which is something the government has said it is looking at.

Also – because to get it off balance sheet it has to operate as a commercial entity – it has to make a 3 percent return on the investment it puts into cost-rental homes, he says.

“The LDA has a built-in set of costs, between taxation, the return and the high maintenance costs which push up their rents,” he says.

Representatives of AHBs point out that Austria’s experience with, and development of, cost-rental stretches back decades.

The Vienna model is operating for more than 100 years and is constantly evolving, said O’Halloran. “Ireland’s only doing this for the last four years.”

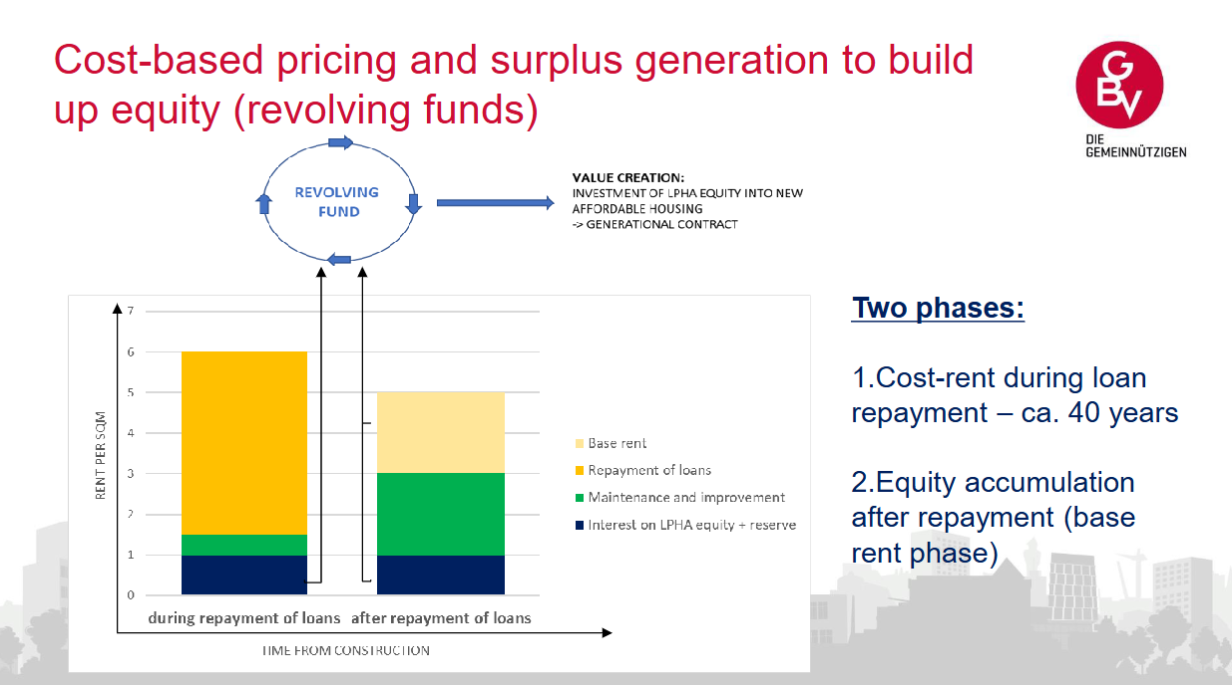

That span means that in Vienna, housing associations have paid off debt on older stock and can channel surpluses from rent collected from those to reinvest in housing as equity – which brings down financing costs and so also the rents, said a spokesperson for Tuath Housing.

Indeed, the scheme in Hirschstetten in Vienna included an equity investment covering 30 percent of the cost and a small equity stake from each tenant – and a low-interest 0.5 percent loan – from Vienna County Council.

Here, the state puts in 20 percent of the cost as equity for schemes funded through the Cost Rental Equity Loan scheme.

But there are ways arguably that AHBs using the Cost Rental Equity Land (CREL) scheme could lower their financing costs, says Ó Broin.

To fund cost-rental projects, AHBs get a primary loan from the Housing Finance Agency, and a secondary loan and that equity investment from the state through the CREL scheme.

Some AHBs, when setting the rents, are recouping the Housing Finance Agency (HFA) loan only – with the intention of refinancing to repay the CREL loan when it has to be paid off.

“But others are charging both the HFA and the CREL repayments at the same time,” he says. “That’s probably worth a couple of hundred euro a month rent.”

O’Halloran, the head of new business at Cluid, says they collect for both. “It’s prudent to set aside based on the loan requirement.”

“If you’re not prudent, setting aside that money to build up over a period of time, it’ll come year 40 and you have a loan to repay,” he says. “It’s a bullet payment, you pay it off at once.”

“That might evolve,” he says. Just as the Vienna model has evolved, he said.

“It needs to be better – of course it does,” he says. “But four years ago, there was no cost-rental in Ireland.”

Ireland has a long way to go to understanding how Vienna has reached rents of €680 a month for new builds, he said. “We have so much learning to do, and we’re going to be doing that as quickly as we can.”

Byrne, the lecturer at UCD, says he agrees that learnings do need to happen.

Project-management skills are so important and he doesn’t think AHBs have them to the level needed, at the moment, he says.

AHBs don’t yet have teams to closely project manage and grind down the delivery costs that feed into rents, he says

Also, Byrne would have concerns, he says, that the current model doesn’t support the AHBs developing in-house expertise. Because when delivery is by private developers, it is those developers who are learning – not the AHBs, he says.

Also, housing associations in Austria do operate at a much bigger scale, and take up a much larger share of the market, than AHBs and the LDA in Ireland.

That larger scale of the housing associations in Austria gives them more leverage, says Byrne.

Byrne says he thinks the fact that all the services, architects and builders – and their relationships with housing associations – have developed within that context of cost-rental too is a big different too.

“I think that there’s an issue around the culture between the relationship between the public and private sector in Ireland and it doesn’t always serve the public interest,” he says.

Ó Broin, the Sinn Féin TD, says the “cost-rental” sector – which he doesn’t even want to call that, he says – in Ireland has too many, too complex, models of delivery, and needs to go back to basics.

Figuring out what rents are affordable to people who earn just a bit too much to be eligible for social housing, and figure out how to deliver housing that can be rented for that amount, he says – with a proposal that includes longer-finance and direct government grants.

“We’ve ended up with rents which for huge numbers of people for whom cost-rental is meant to be available, they’re not able to access it,” he says. “We have ignored affordability.”

On Thursday, Patrick Murphy steered a polka-dot pram with a shopping bag along the footpath on Montpelier Gardens.

In the near distance, the construction site at the old O’Devaney Gardens whirred and chains swang from hooks.

What does he think of the cost rents? Murphy’s focus wasn’t so much on the level of the rents in the cost-rentals or private rentals appearing in front of him – it was on how much social housing there would be on the big sweep of state land.

Just 30 percent of the homes are to be social, he said, dwelling on that for a moment. “It’s just a bit too low.”