Who will sit on the advisory board set to shape the future of Dublin city centre?

Seven areas of expertise should be represented, said a recent council report.

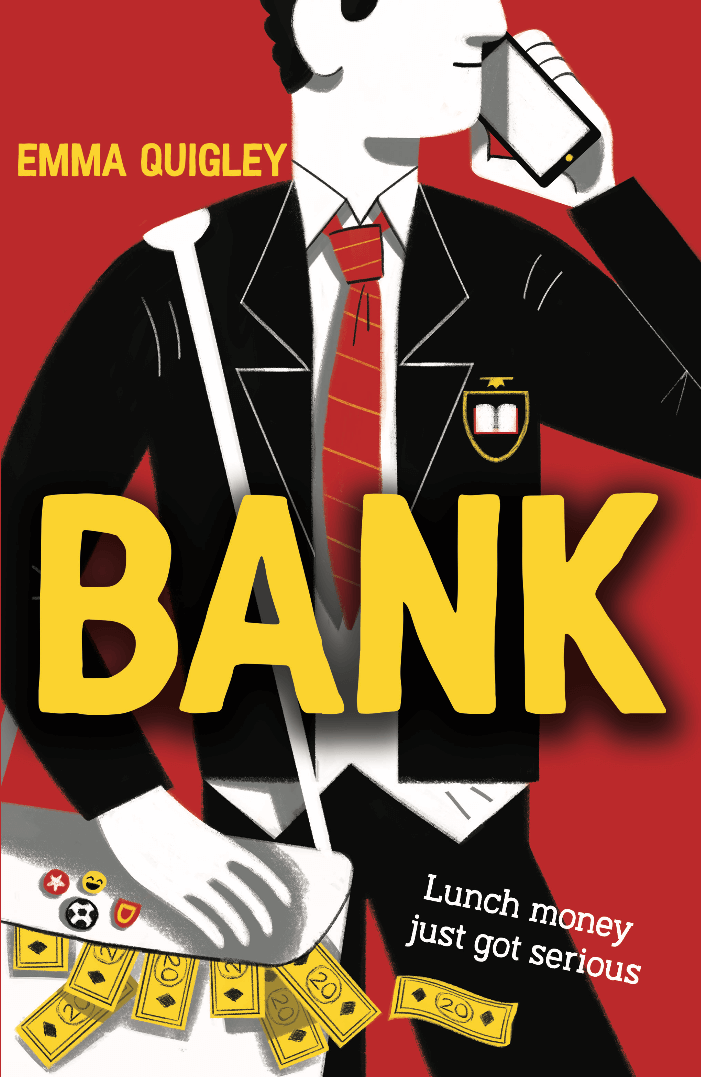

Teenagers turn their hand to banking in Emma Quigley’s debut novel, which captures the complications of adolescence in dialogue that fizzes with energy.

Some might claim to be experts in the field of commerce. But for most of us, economics rarely moves past an enduring wrestle to control personal finances.

Bear-hugging the monthly pay cheque. Leapfrogging the credit-card debt. To-ing and fro-ing with the mortgage, only to be suplexed by an unexpected leccy bill.

Owing to events in this country over the last decade, even those with the merest interest in economics will recognise the volatility of markets. Financial crises are guaranteed, and with them, the continued closure of banks.

This might be something worth keeping in mind if you ever decide to set up your own financial institution, but one thing that is quickly evident in Emma Quigley’s debut book Bank is how young Finn Fitzgerald doesn’t fill his head with thoughts of financial trends or market risk when he decides to do just that.

In fact, beyond the knowledge that the “first rule of banking” is to “never lend the full amount”, Finn admits to not having”a bloody clue”. What he lacks in knowhow, he makes up for in misguided energy, the skill of persistent badgering and a healthy appetite for hard cash.

Once Koby Kowalski is on board (the brains of the operation), Finn quickly coerces his other friends into bankrolling the venture. Their first task is to offer loans to schoolmates in need of financial rescue – with the return of a healthy profit of course.

A work of fiction, aimed at young readers and the young at heart, Bank is told from the perspective of fourteen-year-old Luke Morrissey. Although he is a less-than-enthusiastic participant in the financial start-up, it is Luke’s idea to invest in a match-making app designed by the Hunger Twins, a pair of Doc Martin-clad coders with a limited respect for student confidentiality.

This motivates the bank to shift its focus to an expanding investment portfolio, and they are soon financing the local equivalent of the movie industry, namely Paddy Tarantino, a young lad who specialises in online videos that go viral.

It isn’t long before the success of the bank attracts clients from the murkier end of the spectrum. The mysterious sportswear trader. The betting industry. The fell-off-the-back-of-a-lorry aficionado. A brown-envelope culture is not slow in moving in: free sports-event tickets and the odd uncounted-for muffin.

If the adolescent banking world has a conscience, Luke is it. Albeit, it is a distracted conscience and one that is all too quiet when it comes to standing up against the system.

The fact that Luke’s own family are still reeling financially from the national downturn is a nice touch, adding warmth to the energetic plot. While his friends are splashing out on new gadgets and designer threads, Luke is trying to reduce the household burden by covertly donating cash to his parents.

Fourteen can be an awkward age, involving a questioning of the familiar and a shift toward the unknown. That age for me might well have been summarised as anything Arsenal and the pulling of redners when talking to anyone outside the group. There was also “THAT” coat, the one that resembled a sleeping bag, a fading football crest over the breast pocket.

Still, there were persistent teenage worries lurking behind the scenes, and there’s a certain comfort in reading similar issues in this set of characters – how the core problems haven’t changed too much for the modern teenager, and that it’s still possible to relate.

These adolescent issues are lightly woven through the story, often in a humorous way; the friction with specific teachers, place within the group, the complication of relationships, like the dynamic between Luke and Finn’s cousin Emily, trusted accountant to the group.

A real strength in the book is the dialogue. It fizzes with energy, and Quigley rolls out typical teenage banter with a skill that makes it seem effortless.

Each chapter bursts with imaginative characters, and draws on the reality of those school days where everyone of note has a nickname, often gleaned from a single event or trait that they will never be allowed to outgrow.

“James Bland”, with his monotone voice, as much personality as a wall. Or “The Teletubbies”, so named because of a fight they had in the art supply room where they ended up covered in red, yellow, and blue paint.

In much the same way that the banking crisis in Ireland was predominantly a home-grown affair, a lack of risk-management policies and a failure to regulate puts this youthful banking venture in jeopardy.

Although, the match-making app proves to be the biggest earner, it soon gathers a momentum that’s impossible to control, capturing the essence of the all-too-familiar housing bubble that preluded the crash.

The similarities with the banking crisis are more than just plot-related. There is also the attitude of the participants, the greed and the apathy, that sense of forging onward without considering the consequences.

Adolescents are generally assumed to have moments of self-indulgence. Lacking the confidence to stand out in the crowd means they are likely to take more risks to maintain the status quo, something that might bring to mind those decision-makers in the run-up to the most recent banking crisis, possibly making you question the average age of those who landed the country in such a mess.

But really, that isn’t fair on fourteen-year-olds. Their brains are still developing. They are wired to be self-involved. It’s not as if they really have a choice. But what excuse do the so-called “grown ups” have? Is it more to do with personal experience?

Maybe they missed the toddler life lesson of losing a friend through an overzealous game of shop or a refusal to share their Sherbet Dip. Have they never tried to sell a dodgy action man or Millennium Falcon toy to a classmate for an inflated price, only for a parent to call to the door, demanding their son’s Confo money back?

Or perhaps, unlike Luke Morrissey, they never had to see a loved-one sit for hours in front of a lifeless television set as their hard-earned business collapsed around their head.