Now that the council has stopped taking horse manure, it's piling up in the Liberties

“So the council is allowing horses in Dublin City,” says horse owner David Mulraney. “But they’re not allowing them to put their horse manure anywhere.”

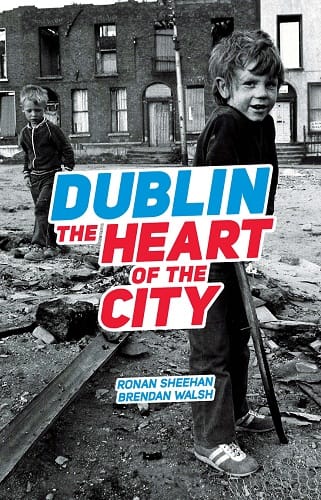

Documenting life of the north inner city docklands in text and photographs, this is a fine historical document, with a few nice literary touches, writes Karl Parkinson.

Dublin: the Heart of the City is a short history of the north inner city docklands of Dublin, or, as they would’ve said there in the ’30s, ’40s, ’50s and ’60s, “the north city centre”, as we’re informed in the book.

It takes in the 1930s, before that the legendary red-light district of Monto, the so-called “New Deal” for housing in the 1980s made by Tony Gregory and one Charlie Haughey, the heroin epidemic of the 1980s, and the concerned-parents movement at the time.

Written by Ronan Sheehan, with photos by Brendan Walsh, the book was originally published in the 1980s, and has recently been reissued by Lilliput Press.

A fair bit of the book is written in a matter-of-fact style, without much of a literary touch, which is to be expected, it could be argued, since it’s not a novel, though I would argue that a bit of style can make any book a better read.

Sheehan is obviously quite capable of this, as is shown in a delicate and beautifully drawn moment when he is in a pub and a shaft of light shines on the old publican pulling a pint, and a kind of Assumption takes place. We’re told it was the last time Sheehan saw the man, who died soon after.

Another well-executed piece of prose is a scene in which Sheehan is drinking with the locals in a pub on Summerhill.

It captures that kind of pub I remember from my childhood, the pool table out the back, the men drinking together and women drinking together, a joint passing around, Sheehan getting the piss taken outta him by one fella who called him Fritz, as he was tall and well dressed, then another drunk getting annoyed and calling him a “queer”. It would’ve been nice if the book had more of those kind of scenes.

The section on Monto, the famous den of inequity frequented by our most famous writer, James Joyce, amongst others, is interesting in its exposure of the church, or more exactly, those perpetual old nosy busybodies the Legion Of Mary, and their founder Frank Duff, who along with the guards and the state had the place closed down. The women’s morals and souls were at stake, you see.

But the poverty and squalor the people in the area lived in was fine. Poor people get their reward in heaven, don’t you know? It must be said that some of the working girls did get help from Duff. But the sex trade, of course, only moved to more underground places, and as long as it wasn’t near the middle classes that was grand.

Throughout the book, we get to hear the voices of many of the working-class people Sheehan spoke to, worked with as a teacher and solicitor, interviewed, and became friends with while working on the book. They give the book a realness and authenticity that would be missing if the only voice we heard was Sheehan’s, which does at times fall into a slightly romantic view of the working class as many liberal or left-wing intellectuals are prone to do.

Sheehan does a fine job of showing how the working-class docklands community was and is continually failed by the church and a succession of right-wing or centrist governments, with Labour falling short too, even before its current decline into farce and political death.

This reached its apotheosis in the 1980s heroin epidemic that plagued the north inner city and south inner city. This part of the book had the most impact on me, as my own father was one of those caught up in it, and I grew up in the second wave of heroin addiction and dealing in the 1990s, which affected the whole generation of men and women of my age.

Sheehan gives a great insight into the Concerned Parents Against Drugs group, which was started by working-class women – mothers, daughters, sisters who had had enough, and weren’t being heard by the government, the law or the media at the time.

Later the movement was joined by the men in the communities also, and then for better or worse, by the IRA.

Sheehan gives some intimate portraits of characters in other sections of the book: a community worker, a prisoner, and Father Peter McVerry, a priest who is one of the good ones, and who does fine and admirable work in the city.

The book ends as the “New Deal” or New Bloomusalem was about to begin. Sheehan asks whether the poor will get what they have been promised. As one who grew up in the north inner city in the 1990s, I can say that we didn’t.

All in all Dublin: the Heart of the City is well worth the read, a fine historical document of the times and the place, of a Dublin before the digital age, a Dublin that seems to be a long time ago, but, paradoxically, for me at least, is still very near.

Dublin: the Heart of the City by Brendan Walsh and Ronan Sheehan (Lilliput Press, 2016)