Things To Do: Store your seeds, seek sanctuary in Naul, accept that the parade is inescapable

Our latest recommendations, and community noticeboard listings.

“Community tool” Anathema is designed to support young artists, undervalued, lost or disillusioned.

Mubarak Ola is quick to point out that he is not an artist. “I couldn’t draw a stickman,” he says.

His background isn’t in the fine arts, but as a food technologist and a culinary arts graduate. He is enamoured, though, he says, by the creative expression of others.

Whether it be a friend or a stranger who finds something awe-inspiring in their mundane surrounds, Ola values what they can tell him, he says.

In turn, he says, he wants to help them in whatever way he can.

Over a coffee in The Bagel Bar on Liffey Street Lower, as the chatter of staff livens up the Sunday morning, the two words Ola keeps coming back to are “amplifying creativity”.

Each time he has involved himself in an arts project, that is what has driven him. The words are practically a mantra.

Dublin is a small community in which there is no shortage of people doing good work, he says. “But some people get the push and others don’t. Galleries only push their artists, you know?”

It is those unexplored pockets of the local art scene that Ola and his collaborators want to illuminate with Anathema, a “community tool” – made up at the moment of a webzine, exhibitions and an event – that they created to support young artists, undervalued, lost or disillusioned.

“We just want a place where you can go find them,” says Ola, with a determined grin.

As Ola lays out this vision, a tall figure in a grey beanie and zipped-up cardigan strides into the cafe.

Offering a spirited and drawn out “Hello” to the staff, he approaches the table, introducing himself as Andrew Kernan, an artist and Ola’s collaborator.

Behind the cafe counter, a coffee machine squeals as it froths milk. Kernan suggests the conversation continue up in the quiet of his studio.

He and Ola head towards a corner of the café, and through a door tucked between a fridge and the counter, and onwards up six flights of stairs.

Kernan’s studio is on the top floor, a repurposed office space that used to belong to an NGO for women called Dress for Success. On the windows, its old red logo has partially stripped off, leaving just the word “success”.

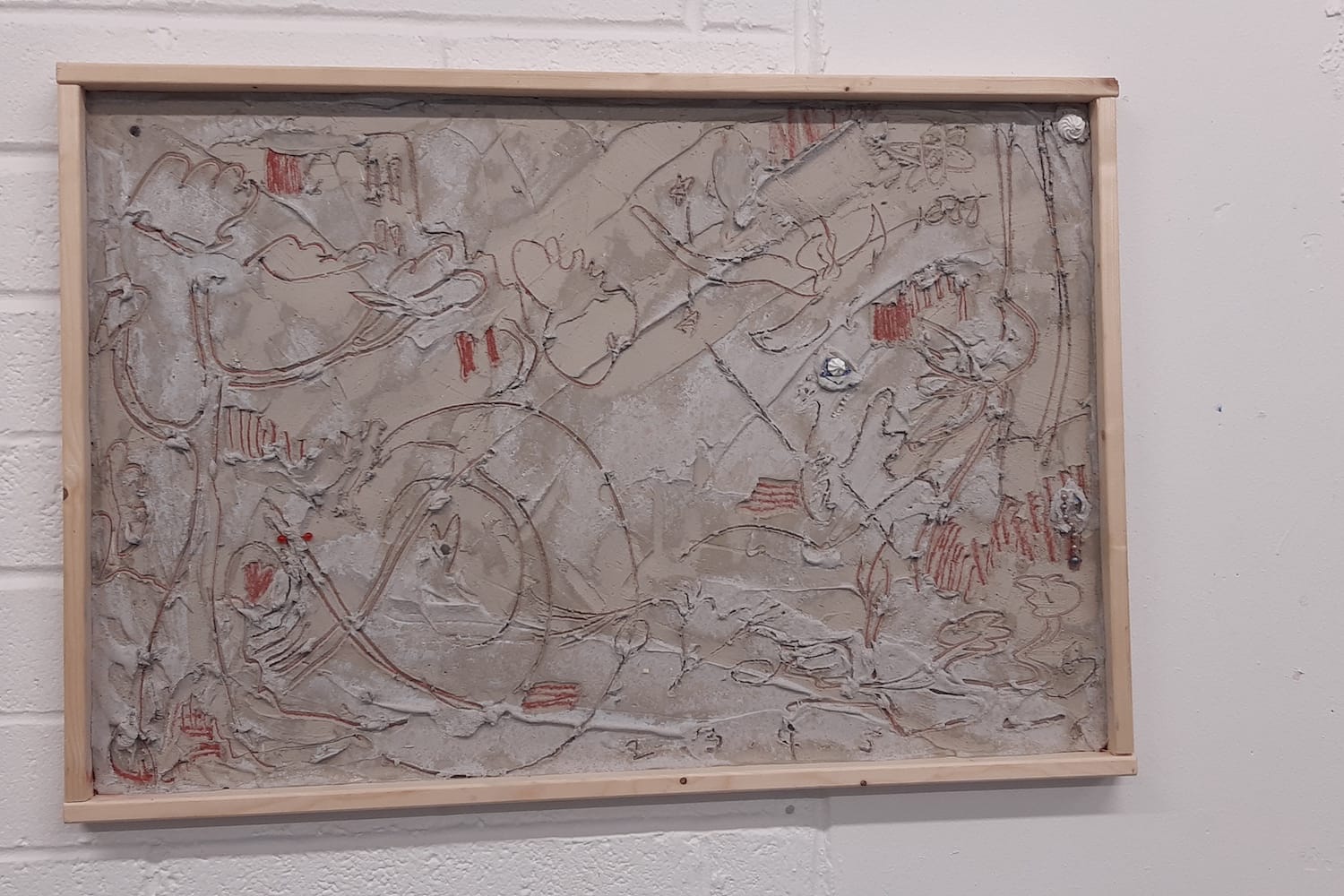

A changing room is now Kernan’s storage space. The walls show some of his larger abstract canvases.

Against the skirting boards, Kernan has propped up five smaller works, pale greys with the occasional husk or blotch of silvery blue.

The subjects are abstract shapes that resemble bare trees in wintertime, and through Kernan’s use of aerosol and charcoal, each one is presented in a ghost-like form.

Ola and Kernan are friends since childhood. They went to the same secondary school in County Meath, and both came to Dublin for college – Kernan to the National College of Art and Design and Ola to what was then Dublin Institute of Technology.

Theatre became part of their life in Dublin, Ola says. Straight out of secondary school, they started in theatre alongside a friend, he says. The Great Unwashed, they called their group.

They staged shows in the Sean O’Casey Theatre in East Wall, beginning in 2016 before wrapping up in 2020.

Kernan says they were on the edges at first. “And then, all of a sudden, we were in it without asking, ‘Can we be involved?’”

Ola laughs. “It was kind of fulfilling an interest to do things. We always had a drive to be like, ‘Do you need a hand?’ Nothing ever formal.”

Anathema grew from this, says Ola.

Anathema, they explain in a written manifesto, is a physical and digital platform. It exists to “lend a voice … to the most exciting and captivating works in Ireland [against] the backdrop of an increasingly disengaged public”.

Online, the intention has been to create a space akin to a digital zine, an unvarnished guide to Dublin’s art scene and an information outlet for and by young artists.

Offline, the focus has been on curation, staging exhibitions that support up-and-coming talent and exploring the issues that prohibit that talent from thriving.

Kernan says he would be reluctant to overemphasise the role of any one individual involved – including himself.

“People tend to tie in names, especially at an early stage before it has its own legs,” he says. “The whole idea is for this to stand on its own.”

According to Finbar Marchant, co-curator of Anathema’s debut exhibition “Brain Drain”, the intention is for this to be “like its own third-party platform”.

“I’m not very interested in accreditation,” says Marchant.

Especially not when it comes to community projects, he says. “Once you have names, figureheads and titles, it takes away from its potency and the potential of what the actual group can do.”

Staged in Unit 4, a Dublin City Council-owned incubation space on James Joyce Street in the north inner-city, Anathema’s inaugural exhibition “Brain Drain” ran 25 to 27 March.

Brain drain is usually associated with emigration, Ola says. “But there is creative brain drain, out of an industry.”

It doesn’t necessarily mean moving away to some place, he says. “It’s also not offering certain opportunities.”

He knows artists who graduated who don’t paint anymore, he says. “That is brain drain.”

Katie Moore, a visual artist from Mayo, says that when she was invited by Kernan to exhibit in the show, the idea made perfect sense.

“I haven’t been too active in my art making in recent years,” says Moore, an artist and mother of two. “I just wanted to be present with my babies.”

Her installation, “Fragility” was a gorse bush that hung from the ceiling like a cloud, she says.

The idea for it came from bringing her children on walks in Mayo, in places where they found themselves surrounded by gorse bushes, she says.

During the walks, she would dwell on questions of security as both an artist and a mother, says Moore. “It explores what it’s like for me navigating life as a new mum and artist living in rural Ireland.”

Of the four artists exhibited, two do not live in Ireland. A fifth, Bill Harris, was forced to pull out after he was offered work in Estonia.

In Harris’ place, curators stuck up a framed email explaining why he was unable to take part.

“When I originally saw the email, I thought this would be a great little piece, because he was planning on doing a performance in the space,” says Marchant.

They messed around with a few ideas, he says, like cordoning off the area and telling people it was a performance. “It just made a lot of sense. It’s creative youth leaving in search of greener pastures.”

Says Ola: “Art should always reflect what is going on around you. Like, you should be present, like a historian, documenting in your own way.”

Kernan is keen to highlight that they intentionally looked beyond their friend groups as much as was possible when curating the event.

“It is bizarre to think everybody does things with everybody that is closest in reach to them,” Kernan says.

This was about bringing people together for those conversations, he says. “And it gelled so well. “Who knows if they would have shown together?”

Ola says the goal is to make Anathema a stalwart in the art community, which as many others as possible can contribute to and access.

“We want people to be like, they know Anathema is where I can get not just information, but help,” he says, “whether that’s directly from us, people with the community or each other.”