Skeletal remains found during construction at Victorian Fruit and Vegetable Market

The bones are thought to come from the major medieval monastery at St Mary’s Abbey, and further excavation works are ongoing.

No decision has been made on whether that will happen, a Dublin City Council spokesperson has said. But it hasn’t been ruled out.

Dublin City Council should look at switching some homes in inner-city flat complexes from social housing into cost-rental homes, a group set up by the Department of the Taoiseach has said.

The interdepartmental group was convened to examine recommendations put out by the Dublin City Centre Taskforce, and set out how to move those forward.

A priority project should be a “precinct improvement scheme”, involving refurbishments inside and out of any social-housing complexes near the core area that aren’t already earmarked for full regeneration, says the group’s report.

“It is advised that Dublin City Council explore the opportunity to provide for some level of cost rental housing within new tenancies in the refurbished flat complexes, and thereby support a broader tenure mix and create accommodation options for some key workers in Dublin City Centre,” the report says.

Switching social homes to cost-rental homes would likely mean, under current schemes, that the council rents the homes to people on higher incomes, but who are still struggling to afford private rentals.

Households with net incomes of up to – depending on household size – between €40,000 and €48,000 are eligible for social homes in Dublin. Those with a net income above that, but below €66,000, are eligible for cost-rental homes.

Such a change in the city’s flat complexes would be pretty significant, says Janet Horner, a Green Party councillor who was until recently the chair of the council’s Central Area Committee.

She can’t see the idea getting backing from councillors right now, she says. “I think at the moment it would be hard to see how you would justify taking away social housing units, I can’t really imagine that getting supported.”

But other councillors say they are more open to, or even supportive of, the idea.

There’s a balance to be struck given the need for social homes, but many people who earn too much to qualify for social homes can’t afford to live in the city centre anymore, said Séamas McGrattan, a Sinn Féin councillor. “There’s more and more people in that bracket.”

Exactly who would make the final call is a bit unclear.

A spokesperson for Dublin City Council said: “Decisions on tenure mix will be made in accordance with council governance structures, involving both senior housing officials and elected members, as required.”

Any consideration of changing homes in flats complexes from social to cost-rental would be guided by analyses of housing needs and community sustainability, availability of funding, national housing policy, and the long-term management of housing stock, they said.

“At present, there is no definitive position on whether specific [council] flat complexes will include cost-rental units,” they said.

Meanwhile, a spokesperson for the Department of Housing said that it “supports a broader tenure mix in the city centre through the provision of cost rental housing for those above the social housing income threshold”.

It is happy to work with the council to explore the opportunity of providing some cost-rental tenancies within refurbished flat complexes, they said.

One of the 10 “big moves” put forward by the Taoiseach’s taskforce for the city centre, led by An Post CEO David McRedmond, was to “prioritise the total regeneration of social housing complexes”.

Dublin City Council already had regeneration plans for many complexes. Sixteen projects in and around the city are listed in a recent update – like the stalled retrofitting of Pearse House, and the demolition and rebuild of St Andrew’s Court.

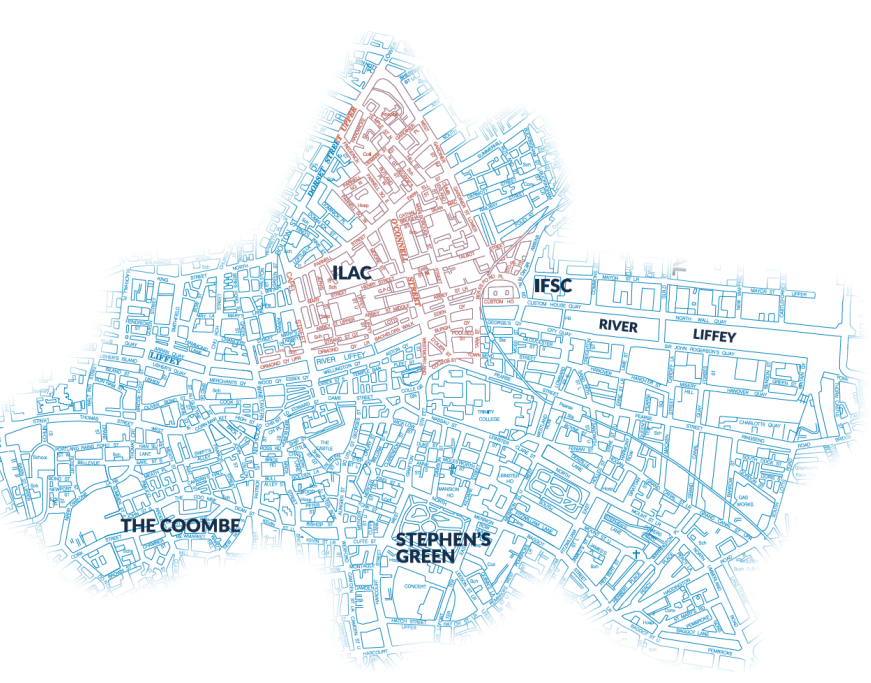

It’s other complexes in the wider area, those in need of less work, that fall under the proposal to move to some cost-rentals, according to the interdepartmental group’s report.

McGrattan, the Sinn Féin councillor, says he thinks it would therefore be a small number. “I don’t see this being a huge issue. Most of the complexes are down for regeneration.”

Still, it would be a significant change of policy.

Creating what are known as “mixed-tenure” developments – so, varied blends of social homes, cost-rentals, affordable-purchase, market-rate rentals, and market-rate owner-occupied homes – has been government policy for decades.

But, save for cases of demolition and regeneration – such as on Charlemont Street, or O’Devaney Gardens – social-housing flat complexes have been untouched by the push for mix, says Fiadh Tubridy, an activist with Community Action Tenants Union (CATU).

Which is good, as it has helped preserve them as social homes, until this proposal, she says. “It’s a pretty radical proposal in a very negative way.”

Proponents of tenure mixing say that it is a way to deal with “neighbourhood effects” that arise with concentrations of deprivation, such as stigma, and poor access to services.

Critics say that tenure mixing responds to the symptoms of spatial inequality but does not address the underlying issues of income inequality or access to services, and can increase senses of difference.

Housing Agency research from March 2022 that looked at five housing estates where approved housing bodies (AHBs) own social homes alongside private homes found that, overall, the estates had settled well into strong communities. But design, and the mix in the wider area, are also important to consider, it said.

It’s not completely clear what the interdepartmental group – which included representatives from the council and the Department of Housing – would be trying to achieve by making some social flats into cost-rentals.

A spokesperson for the Department of Housing hasn’t responded to a query sent on Thursday, asking whether it is simply to provide homes for those on higher incomes who are still squeezed, or whether they see other benefits.

Tubridy, the CATU activist, who is also a post-doctoral researcher on the Just Housing project at the University of Maynooth, says that the idea that a mix of tenures is needed for a functional community is outdated.

“These are really hacky ideas that have been trotted out for so long and are manifestly untrue,” she says.

Estates being rundown and poorly maintained, residualisation as some higher-income social tenants move out, and drug problems with a lack of supports are what can drive problems, she says.

She points to Emmet Buildings, a complex on the edge of the Liberties where CATU and social housing tenants have been campaigning for better conditions and refurbishment of their homes.

There is such a strong community for generations, who want to stay there and love their area and neighbours, she says. “The idea that you need to introduce tenure mix to make it functional is crazy.”

Independent Councillor Cieran Perry, however, says that he would anticipate benefits from mixing some cost-rental flats into social complexes – although he would frame it a bit differently to the interdepartmental group.

“I think it’s a great idea,” he said. “I don’t necessarily like the term tenure mix, but I like the term income mix.”

There can be a small number of households engaged in anti-social behaviour in social-housing estates, he says, which has long been a focus of his.

“My big issue is and always has been anti-social behaviour in our estates and developments. That’s the primary concern for people,” he says. “The anti-social behaviour is getting worse.”

Bringing in tenants on higher incomes would help with that, he says, as they would have louder voices to push for better social-housing management. “There’s lots of disadvantaged people in social housing who have been forced to accept lesser service.”

Deirdre Heney, a Fianna Fáil councillor who is chair of the council’s housing committee, said she wouldn’t necessarily be in favour of changing the tenures in complexes.

“I’m not saying I would particularly like us to take from the social housing units that are there. No, I’m not,” she says.

But if the council does take up that recommendation, she would push not for the conversion of flats to cost-rental homes, but rather to homes that people could could buy at an affordable rate and live in, she said.

That’s based on what constituents come to her asking for, she says. “I would think that you’re better off doing that, from my own personal experience and dealing with the public in general.”

Catherine Winston, who lives in a social-housing complex called Wolfetone Close, which is tucked away in the city centre near Jervis, said she had tried to buy her flat several years ago.

That was through the tenant purchase scheme under which social tenants can buy their homes. But she wasn’t allowed – because the scheme is only for social tenants in houses not flats.

She was told it would be too difficult given the need to manage and maintain the common areas, she said.

There’s no indication whether Wolfetone Close would be one of the complexes considered under the proposal to mix in cost-rental homes.

But Winston isn’t convinced of the idea of converting some flats anyway, she says. “It wouldn’t be a good idea. It would cause friction in all sorts of ways.”

If some people are paying lots more for rent or services such as bin charges that could be a real point of tension, she says.

The position of Perry, the independent councillor, is that in an ideal world there would be universal public housing – so anyone on any income could access a council home, and pay an affordable rent.

“But even those of us who have been pushing that for years, get that this isn’t an option right now,” he says.

A closer look at the impact of converting social homes to cost rentals on the social-housing list would be needed, said Perry.

As of July 2024, there were 14,967 households on the main social-housing list, and 16,083 on the transfer list in the Dublin City Council area. Of those, 7,158 households have been waiting more than 10 years.

Perry says he has been conscious of how common it is for constituents to come to him these days and say they have been waiting a decade for a social home. It was so much rarer when he started as a councillor, he says.

Switching some flats to cost-rentals would limit choices for people looking for social homes, he says. “But I think that the concept of mixed-income is important so I would have to support it.”

A spokesperson for Dublin City Council said that it is “committed to ensuring that any decisions taken on tenure mix in a development does not undermine our responsibility to also provide housing for those in greatest need on our social housing waiting lists”.

McGrattan, the Sinn Féin councillor, said there is huge demand in the city centre for affordable rentals targeted at key workers who aren’t eligible for social housing.

Also, some complexes in the city centre don’t have massive demand at the moment because of conditions, he said. Although, of course, any refurbishment would drive that demand up, he said.

Horner, the Green Party councillor, says she understands the frustration with the lack of affordable options for those stuck in the private-rental market and earning too much for social housing.

She’s on the board of the Rotunda Hospital, she says, and knows they struggle to attract staff because of a lack of affordable homes in the city centre.

“They’re very interested in looking at models to support cost-rental or something equivalent,” she says.

Still though, only if there was a massive increase in social housing could they afford to convert existing flats to house those on higher incomes, she says. “But that isn’t available.”

Limiting any possible future cost-rental flats to “key workers”, and coming up with a definition of that, is something that would need greater thought, said Perry, the independent councillor.

It would add complexity and an administrative burden, he says, although there are arguments for ensuring nurses can live near hospitals or for guards to live within communities. “Maybe that just needs to be fleshed out.”

McGrattan said that which complexes would be proposed is also important.

It’s something councillors need to input on with their understanding of local context, he says. “I think in some of the larger complexes it would work but not the smaller ones.”

Tubridy, the CATU activist and academic, says she takes issue with the suggestion that cost-rental homes are needed for key workers, and an implication therefore that council tenants don’t do socially productive jobs.

“Not that whether you are in employment is a mark of your value, but so many council tenants are in work and working in important jobs,” she says.

The idea of transitioning social housing to cost-rental homes – whereby the rents are set to cover the costs of delivering, financing and managing the homes over a long period – isn’t new.

In May 2024, the Housing Commission recommended that, over time, the government look at migrating all social housing to cost-rental housing.

“This would allow for a more stable and financially sustainable form of housing provision and reduce issues with gaps in eligibility limits,” its members said in a report.

It would “provide a sustainable financing model for social housing by setting social housing rents at cost recovery rates”, the report said. And, it would also “ensure there is sufficient income to manage and maintain dwellings” and “assist in funding new social housing provision”.

Although, its report says, changes should be made alongside other measures, as a package. Including, “to ensure that rents remain affordable, housing allowances should be provided to subsidise tenants who cannot afford to pay full cost rents”.

Meanwhile, Dublin city councillors have been looking at whether to increase rents in social housing, as a way to find more money to improve standards, after years of complaints about poor maintenance.

Winston, who lives in Wolfetone Close near Jervis, says she and other tenants have been asking for years for new windows. Theirs haven’t been replaced for almost 30 years, she says.

But tenants are effectively penalised if they run out of patience waiting for the council to renovate their homes, and pay for works themselves, she says.

Take a neighbour who really needs a shower put in, she says. They can’t use the bath because of poor mobility and so wash in the sink, she says.

If they were to pay for a shower themselves, the council warns that they won’t ever fix it if it breaks, she says. “They really need to change that rule. You shouldn’t be punished.”

Horner, the Green Party councillor, said that councillors have bumped up allocated funding for social housing maintenance. They hope the department will match those funds, she says.

McGrattan doesn’t think the proposal from the interdepartmental group to refurbish some complexes and mix in cost-rental would do much to help with sustainable funding for maintenance, he says.

Cost-rental tenants would be paying a higher rent than the social tenants. But “that money isn’t necessarily ringfenced for that complex and it’s a small scale so I don’t know if it would have an impact there”, he says.

Tubridy, the CATU activist, says she now worries that moves to improve and retrofit or refurbish city-centre complexes could be tied to the idea of higher rents for new tenancies, with the conversion of flats to cost-rentals.

She sees that as a climate justice issue which mirrors “renovictions” of the private-rental sector, she says. “It’s making access to decent housing dependent on changing the social make-up of the flats.”