Tusla says it's an offence to run an unregistered children’s home, but it places children in them anyways

So how does it square the circle?

Those working in Dublin’s north inner-city reflect on its “golden age” of community development – and draw varied lessons that resonate today.

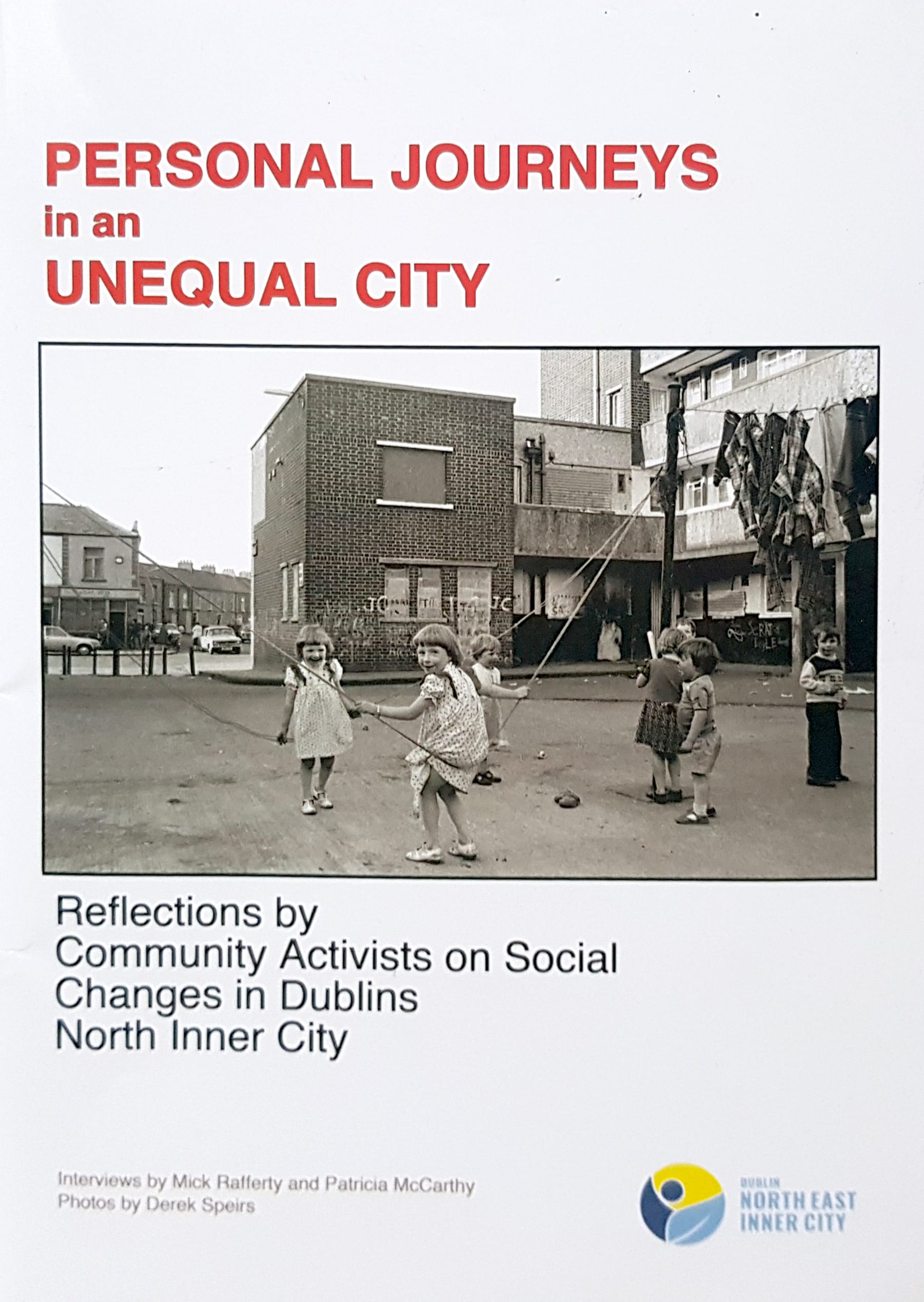

Personal Journeys in an Unequal City is a new collection put together by long-time community organisers Mick Rafferty and Patricia McCarthy – a series of in-depth interviews with respected figures from the community-development sector in Dublin’s north inner-city.

It focuses on what is described by many as its “golden age” of community development – a roughly 20-year stretch between the late ’70s and late ’90s. During that time, the emergence of a drugs epidemic in the area began to have a catastrophic effect on communities. One impact, albeit in painful circumstances, was to politicise people and foster a strong sense of solidarity among those affected.

Another crucial moment was, of course, the election of independent TD Tony Gregory to Dáil Éireann in 1982. The subsequent “Gregory Deal”, when he held the balance of government power, led to an injection of funding into the community that ordinary activists had been demanding for years. While the Dáil ultimately dissolved after only six months, and the re-elected Fine Gael-Labour coalition failed to deliver on many of the promises of the Gregory Deal, it was a brief and energising victory.

While each of the interviewees in Personal Journeys in an Unequal City was active in the community during this “golden age”, they draw varied lessons as they look back. Some of that comes from differences in background, some from differences in politics.

In all the interviews, Rafferty and McCarthy emphasise the interviewees’ personal journeys – and in doing so they contextualise and humanise these testimonies so that even a complete outsider would come away with a solid grasp on the issues being discussed. A common flaw in reflective literature such as this is an assumed prior knowledge. Personal Journeys doesn’t make this mistake.

In the book’s first interview, Tessie McMahon talks about the transformative effect of attending her first North Wall Association meeting in 1975. After growing up in St Bridget’s Gardens flats and briefly moving to Birmingham with her husband, she returned to the city, but found it tough to find suitable housing. This frustrated her. But it wasn’t until she got involved with the North Wall Association, she says, that the frustration morphed into action.

She quickly went from there to attending local council meetings, to establishing a community playgroup and, ultimately, becoming a member of the North City Centre Community Action Project (NCCCAP).

Many of the contributors in Personal Journeys speak about the impact the NCCCAP had on them. It’s embodied best by McMahon.

In contrast, Anna Quigley’s early experiences were as an outsider. Quigley was raised in the comparatively cushy environs of Stillorgan, and pursued a social science degree in University College Dublin.

She speaks about graduating, ostensibly qualified to work in the community sector, but lacking the knowledge of the local area and its people that a degree simply couldn’t impart. This testimony is damning in the context of a sector that increasingly – and especially now – prioritises formal education above real-life experience. Quigley was cognisant of this at the time and flags it as an ongoing issue for the sector.

Perhaps the best-known voice in the anthology is that of Fr Peter McVerry, a public figure by virtue of his many years working with the city’s homeless population. Having grown up in a middle-class family in Newry, McVerry’s formative experiences greatly contrast with those of the young people he has spent so long advocating for.

He reflects on establishing links in the north inner-city, basing the work of his organisation on friendship and mutual respect. Distrust of establishment institutions and figures of authority was unanimous among young people at the time, so McVerry worked on building mutual trust.

Most of the interviewees in Personal Journeys reflect on the devastating impact of containerisation in the north-east inner-city. There was mass redundancy of dockers, as their well-paid heavy labour – which had sustained families for generations – was replaced with shipping containers for cargo.

The state didn’t intervene to ensure new jobs or training for those affected. That neglect was coupled with a dereliction of investment in the physical environment of the area – most notably around Sheriff Street – and rapid decline followed.

In Fergus McCabe’s interview, he touches on the noticeable shift away from an emphasis on true community development towards a more bureaucratic casework model in his experience as a psychiatric social worker. In essence, this meant that individual cases took precedence over addressing structural inequalities.

There was a wealth of capable organisers in the local area, but they were held back by educational disadvantage and “the vested interests of outsiders”, he says. This underlines what he describes as a hostility from bureaucrats in the civil service towards the empowerment of local people.

While Personal Journeys is very much a reflective publication, looking back at lifetimes of community work, it draws on themes that remain hugely significant today. The issue of managed decline, of a sense of the city council prioritising business interests above community, is touched on by several of the interviewees.

McCabe points to the appointment of John Garvin as city manager of what was at the time Dublin Corporation, as key in the body’s shifting priorities. The emphasis, McCabe says, moved towards reducing housing stock in favour of identifying office and business space. This manifested itself in allowing council flats and land to fall into disrepair, forcing residents out and selling off land to private developers – the underlying principle of “managed decline”.

McCabe pinpoints this shift as starting in the late 1960s, but its long shadow has stretched through to today – to the International Financial Services Centre, and the wider Docklands, and further to O’Devaney Gardens, and the broad and deepening housing crisis and hotelisation of the city we see today.

John Farrelly’s testimony, meanwhile, captures a lament on what he describes as a “lack of mass consciousness” around social issues in the area. While the rise of community initiatives in this aforementioned “golden age” of the sector empowered people to, say, fight for a house, there wasn’t a collective joining of the dots on why their individual fights were necessary, he says.

To this end, Farrelly believes that while direct interventions were important – protesting, squatting, on-the-street organising – he stresses that analysis is key to moving forward, evaluating the tactics that did and didn’t work, and gleaning lessons for the future.

Personal Journeys offers readers an accessible and informative overview of a community that is often misunderstood, and even infantilised, in analysis. Crucially, it is composed exclusively of the reflections of those who lived and breathed it over many years.

Academic reviews of areas like the north-inner city, and sectors like community development often suffer from being conducted from outside. As Anna Quigley put it herself, no amount of qualifications can compensate for lived experience. This publication dedicates itself to that lived experience.

While it is predominantly reflective, many of the interviewees are also asked for their assessment of the sector today.

Fergus McCabe offers a reasonably optimistic insight, that positive outcomes are possible if the state makes good on promises for regeneration set out in the Mulvey Report, published more than two years ago after a string of drug-related shootings in the area.

Most, however, are not as hopeful. Fr McVerry says he sees little cause for optimism. There is no evidence, at a government level, of a commitment to policies that will deliver tangible, long-lasting change, he suggests.

If there is one failing in the book, it is that it overlooks a lot of the positive work being done in the sector today. There are young organisers throughout the community following in the footsteps of those interviewed here. A nod to their work in assessing the sector in 2019 would perhaps have been welcome – even alongside the necessary criticisms that are made.

Overall, however, Personal Journeys in an Unequal City offers authentic and telling insights into this wonderful complex community. It is produced without any prior assumptions of the reader’s level of knowledge, so its prospective audience is vast. The testimonies are enlightening – heartbreaking in parts, uplifting in others.

It’s essential reading for those with an interest in the community sector, but has more than enough to keep a more casual reader engaged, too.