On the walls of a Kilbarrack health centre, an artist pays tribute to the beautiful ordinary

Paul MacCormaic says he hopes the works inspire an interest and pride in nearby sights, passed by everyday.

We should spend more time thinking about the social, political, and environmental complexities of Ireland’s role in the Internet, writes a DCU PhD researcher.

Walking Sandymount or Dollymount strands, you’ll encounter some people out jogging, others letting their dogs play with the tide as it comes in or rolls back out, and others staring out at the endless horizon in front of them, lost in their thoughts.

There are some things you won’t notice, however. Such as the cables buried underneath the sand that connect the city behind you to rest of the world.

Ireland’s position as a “global technology hub” is well known, evidenced by the many international tech companies with bases here, including Amazon, Facebook and Google. Perhaps a little less well known is for how long Ireland has been a tech hub.

It didn’t start with the Celtic Tiger years and the redevelopment of Grand Canal Dock. Some tech companies have been here a lot longer. IBM opened an office in Dublin in 1956. Apple has been in Cork since 1980, and it was followed a few years later by Microsoft, which established a manufacturing facility in Ireland in 1985.

However, today’s narratives surrounding Ireland as tech hub form just a small part of a story that began over 150 years ago. As an island in the Atlantic, between America, England and mainland Europe, it has transferred important data since the mid-19th century, through cables that lie beneath the sea, making it an important location for both the corporate and physical backbone layers of the Internet.

This explains why Ireland has been an important location for the covert operations of various spies and intelligence agencies. And it also means that we should spend more time thinking about the social, political and environmental complexities of Ireland’s role in this global network on which all our lives rely so heavily these days.

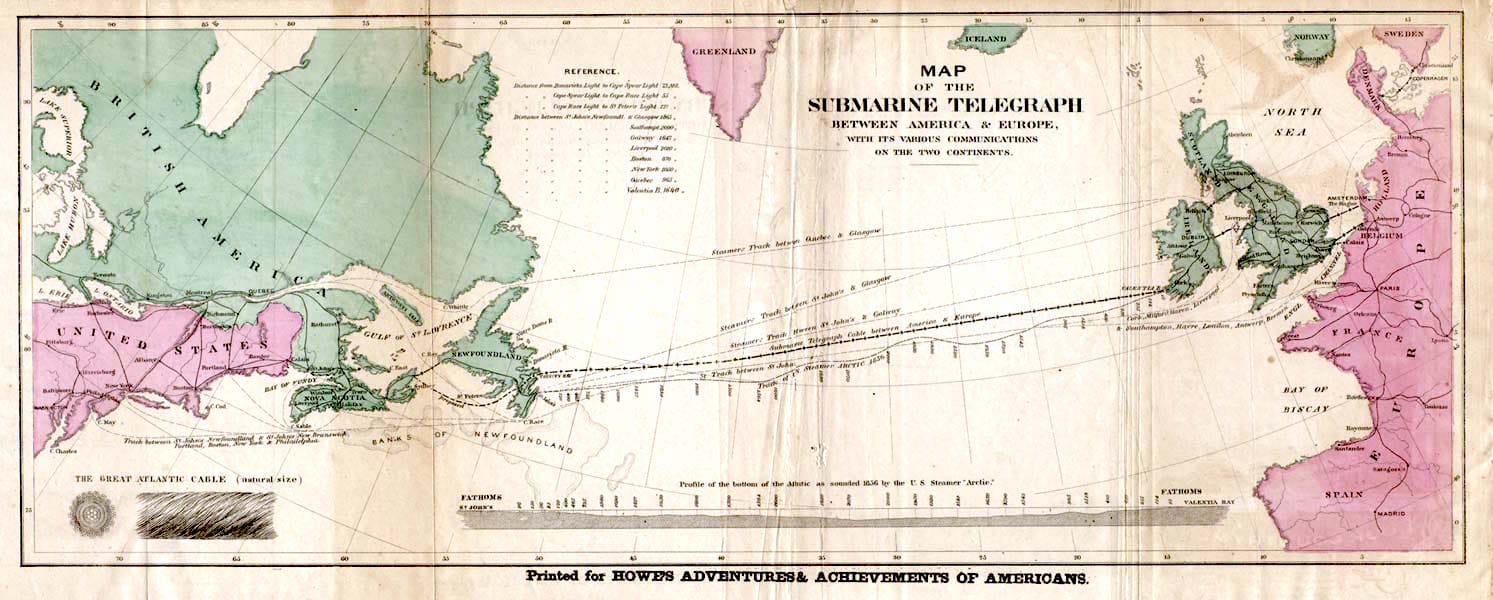

The first transatlantic cable, completed in 1858, stretched from Newfoundland in Canada to Valentia Island off the coast of Kerry. It only worked for three weeks.

They tried again, and finally laid a more durable cable in 1866. “A treaty of peace has been signed between Austria and Prussia,” read its first message.

This was not to be the only time Valentia Island was a key node in the transfer of military information. On Easter Monday 1916, Kenmare postal worker Rosalie Rice brought news of the unfolding events in Dublin to her two cousins, Tim and Eugene Ring, who were working as telegraphers at the Valentia Island cable station.

Tim Ring was also a member of the Irish Republican Brotherhood. When he got word of the rebellion in Dublin, he sent a prearranged coded message to John Devoy, leader of Clan Na Gael in New York, telling him that the Rising had started. “Mother operated on successfully today in Dublin. Signed Kathleen,” it read.

This clandestine message meant that Clan na Gael were aware of events in Dublin before the British government in London. Indeed, confirmation of the Rising would come from the British ambassador in New York, who had also seen the cable.

Fast forward almost a 100 years and we find another example of the British government accessing information passed through subsea cables.

Documents released by NSA whistleblower Edward Snowden in 2013 revealed that British intelligence, specifically (GCHQ), had been targeting subsea telecommunications cables, including some with landing points in Ireland.

Effectively, this meant GCHQ was able to extract massive amounts of personal data generated from the internet traffic passing through these underwater cables. The surveillance programme, called Tempora, was carried out with the cooperation of the owners of these cables.

This, of course, begs the questions: who owns them?

The first transatlantic cables were telegraphic. These were used until they were replaced with telephonic ones in the mid-20th century.

Then, in the 1980s, telephonic gave way to fibre optic. Fibre optics are small strands of glass that can transmit data through wavelengths of light.

Subsea fibre optic cables are “critical infrastructures” that support our global networked society, according to Nicole Starosielski, an associate professor of media, culture and communications at New York University (NYU).

It is estimated that subsea fiber-optic cables transmit 97 percent of global digital communications, including our emails, text messages, tweets and phone calls.

According to Telegeography’s submarine cable map, there are eighteen active subsea cables landing that land up on the island of Ireland – thirteen in the Republic. These vary dramatically in length.

The shortest is the Emerald Bridge Fibre cable, co-owned by the Electricity Services Board (ESB) and American infrastructure services company Zayo Group. It’s roughly 120 kilometres long, active since 2012 and runs from Clonshaugh in North Dublin to Holyhead in Wales.

The longest, at 12,200 kilometres, is the GTT Atlantic cable, operated by the multinational telecommunications and internet provider company GTT Communications. It has landing points in the Republic, Northern Ireland, the United States and England.

The ownership of the subsea cables is often as complex as the routes and landing points they travel along, with company takeovers and mergers resulting in cable name changes.

The GTT Atlantic was originally developed by 360Networks, before being acquired by Hibernia Networks, which in turn was taken over by GTT Communications in 2017, while 360Networks was bought by the Zayo Group in 2011.

Aqua Comms, an Irish company, founded in 2014, and the operator of various cables landing in Ireland – including the America Europe Connect-1 (AEC-1) and CeltixConnect-1 is the outcome of various acquisitions and mergers of companies such as Emerald Networks, Sea Fibre Network and Aqua Ventures Limited.

Other investors at various stages over the last two decades include various Irish corporate entities including Esat and Eir, alongside international telecommunications companies such as British Telecom, CenturyLink, Orange, Vodafone and Virgin Media.

Nowadays, actual content providers are getting involved in the development of subsea cables.

The America Europe Connect-2 (AEC-2) cable is expected to be active by the end of this year and will have landing points in Ireland, Denmark, Norway and the United States. It is being built by a consortium featuring Aquacomms, Bulk Infrastructure, Facebook and Google.

We now know who owns the cables, but how do we actually find them? The Kingfisher Information Service – Offshore Renewable & Cable Awareness (Kis-Orca), provides maps and charts for fishermen and women to use in navigation.

We can also consult the “foreshore consenting” section of the Department of Housing, Planning and Local Government; companies are obliged to apply for a foreshore licence for any subsea cables landing in the Republic of Ireland.

Of the thirteen cables landing in the Republic, five active cables do so in and around Dublin. These land between the Lusk-Rush area and Sandymount.

The landing points of these cables are presumably close to cable landing stations such as those in Clonshaugh and Eastpoint business parks. These stations are located near to the T50, a 44-kilometre fibre-optic cable that follows the route of the M50 motorway around the city from Clonshaugh to Clondalkin and, as such, connects the many data centres surrounding the city to the rest of the digital and physical world.

Proximity to the Irish Financial Services Centre (IFSC) and Silicon Docks should not be overlooked either. Subsea cables, of course, carry financial transactions – close to €9 trillion worth of financial transfers globally each day, some estimate.

“Financial information now travels at the speed of light; but the speed of light is different in different places … [T]he greatest prizes go to those with the lowest latency, the shortest travel time between two points,” artist and author James Bridle notes.

These subsea cables, in a way, reflect geopolitical realities. While digital culture always evolves, the supporting physical infrastructure of the Internet does not,

Starosielski, of NYU, has said. It is, she argues, built along historical and political lines that seem to reinforce “existing global inequalities”.

All of the subsea cables mentioned earlier connect to either the United States or the United Kingdom, reminding us of Ireland’s complex historical relationships of migration, trade and colonialism.

Migration and trade continue to this day. It is not confined just to people and goods, but also data. Issues such as data sovereignty and GDPR make Ireland today a key location in storing and transferring data, as it was 150 years ago.

We can even see a post-Brexit world emerging in these cables: the Ireland-France Subsea Cable, ready for service in 2020, landing in Cork and Lannion, France, will bypass the United Kingdom.

Now, back to the Snowden revelations mentioned earlier. Since 2013, journalists have told more stories of espionage and subsea cables.

In December 2017, it was widely reported that Russian submarines were spotted near subsea cables in the North Atlantic, along a route with many cables connecting America to Europe, some of which, as we have seen, pass through Ireland.

However, tapping these cables isn’t a new practice. It’s been happening since well before the Russians or even GCHQ. Operation Ivy Bells was a 1971 NSA-led plan to wiretap a Russian subsea cable between two Soviet naval bases in the Sea of Okhotsk in the Pacific Ocean.

So the question is not about how to secure subsea cables from being monitored or tapped. We should assume that they are.

As Laura Nolan, a former software engineer for Google and founder of Tech Won’t Build It Dublin, told me, “Encrypting everything is the solution, not physically securing the cables. Modern best practice is to assume everything is tapped, because you’ve no way of validating that it isn’t.”

That said, there are worries of potential physical sabotage of cables or cyber attacks on the network-management systems that control cable infrastructures – essentially a kill switch that could disrupt Internet connectivity within a whole region.

Whilst these doomsday scenarios are unlikely, they compel us to ask questions about our understanding of not just subsea cables, but other core components of the Internet’s backbone, passing through Ireland and beyond.

Science Fiction author Neal Stephenson has argued that using the Internet without understanding the “wires” that support it is the same as using petrol for your car without considering where the petrol came from. In his words, “that works only until the political situation in the Middle East gets all screwed up, or an oil tanker runs aground on a wildlife refuge”.

Stephenson wrote that almost a quarter of a century ago. But it still rings true. We grow ever more dependent on the Internet in our everyday lives, yet our awareness and consideration of the material, political and economic processes behind it remains limited.

This can be attributed, in part, to our own apathy. Once we can update our statuses, message our friends and family in far off places, hail a taxi or order food, all with a few swipes and clicks, do we really need to worry about anything occurring beneath the interfaces we now constantly engage with?

However, this apathy is reinforced is by the opaqueness associated with corporate-tech terminology. Take “the cloud”, for example. A word that discourages users from critically questioning or engaging with the material actions that take place behind our everyday interactions with the Internet. If we are to empower ourselves through technology – and challenge its darker aspects – we need to excavate and untangle the complex structures of the corporate-tech black boxes that so much of our contemporary networked society is built upon.

The “cloud” is not ephemeral and here in Dublin it’s all around us. It’s in the devices in our hands, under the manhole covers of the streets we walk, in the corporate HQs of Grand Canal Dock, in the industrial estates and business parks along the M50 motorway – and of course, in those cables that stretch out into the sea.