A new council sports forum looks to press schools and such to share their facilities

Amid a serious shortage of pitches in Dublin 8, the OPW only allows one soccer club to use its pitch at the War Memorial Gardens.

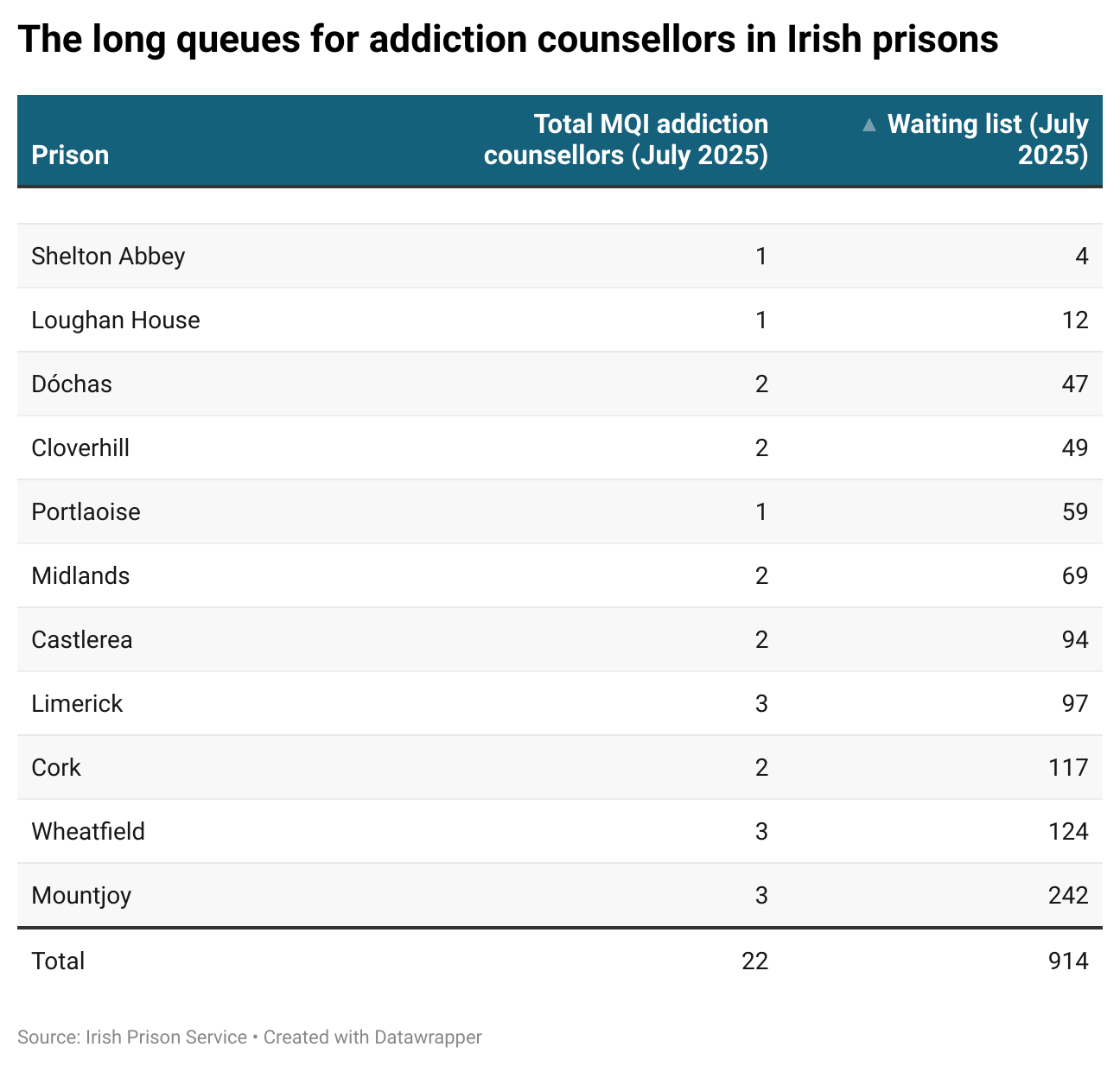

The longest queue is in Dublin’s Mountjoy, where more than 240 people languish on the waitlist for counselling for substance addiction.

More than 900 people in custody in prisons across Ireland are on waiting lists for addiction counsellors, show figures from the Irish Prison Service (IPS).

The longest waitlist, the figures show, is in Mountjoy men’s prison.

There are currently 1,193 people within the system at Mountjoy, with 975 of those actually in custody.

Of those, there were 242 men in Mountjoy (25 percent) on a waiting list to receive treatment for substance addiction, show the IPS figures

Meanwhile, on 30 June, 565 of people in custody at Mountjoy (60 percent) were on a waiting list to receive mental health treatment, show IPS figures.

A year ago, then Green Party TD Patrick Costello asked the then Justice Minister Helen McEntee whether the IPS was following best practice, after a spate of overdoses in one facility.

McEntee’s response focused on how the IPS prevents contraband from entering prisons, and drug testing.

“The reality is that those with active addiction continue their drug-seeking behaviour inside prison notwithstanding the supports that are available to address their addiction,” she said.

A spokesperson for the IPS says that upwards of 70 percent of people in prisons across Ireland are experiencing some form of substance addiction. It’s the same figure quoted by IPS officials back in 2017.

But today, that may be a conservative estimate, says Eddie Mullins, former governor of Mountjoy Prison and current CEO of Merchants Quay Ireland (MQI), which operates drug and homeless services.

MQI is contracted by the IPS to provide addiction treatment services in prisons across Ireland – including Mountjoy.

But demand for those services far outweighs the current resources, Mullins says.

“If you look at what we would call the general population, it's almost impossible to find somebody who hasn't or doesn't use drugs in prison in the ordinary population,” Mullins says.

“Prison is the sort of environment that drives you to use drugs,” says Fr Peter McVerry, homelessness campaigner and activist.

McVerry says he knows many individuals who only began taking drugs while incarcerated.

“They went to an overcrowded prison sharing a cell with drug users. Prison is a boring, demoralizing environment to be in. You have nothing to do,” he says.

Prisons were never set up as therapeutic environments, Mullins says.

They’ve gradually improved across the years, he says. Services like counselling and detox programmes now exist.

But still, they are detention centres first and foremost, with a primary objective of keeping those incarcerated safe, and society safe from those in prison, he says.

“I often wonder, are we putting too much expectation on the prison system?” Mullins says.

Investment should be redirected into alternatives to prison, with an emphasis on recovery, addiction and detox supports, he says.

Even for those who are fortunate to receive treatment while they are incarcerated, Mullins says, it is not an easy road maintaining the work they’ve done.

Day to day life in prison is fraught with temptation, he says.

The current Programme for Government pledges to build 1,500 new prison spaces. McVerry would rather see 1,500 new residential drug treatment places, he says.

That would be far more effective in reducing crime, he says.

Going back over the last 20 or 30 years, McVerry says, every time we build more prison spaces, they just get full, overcrowded and so more are built.

“Of course, politically, that's a winner. Because the public are delighted to get them off the streets. But without realising, this is not effective,” he says.

The Treatment and Recovery Programme (TARP) run by Merchant’s Quay Ireland in Mountjoy Prison lasts eight weeks, says Karl Duque, its coordinator.

It is intensive, he says, with nine participants per cycle.

Mountjoy hosts the programme, but participants may be sent from other prisons around the country on recommendation from counsellors.

They have to be already engaged within a service, Duque says.

That can include counselling, education work, or even going to the gym – once they show consistency, he says.

They must also be free of disciplinary reports, known as P19s, for three to four weeks.

Once on board, participants are kept separate from the general population in a sterile environment, he says.

Visitation is done with screens between them and their family to ensure no drugs are brought in. They are allowed extra phone calls while on the programme.

TARP participants must be drug-free to attend.

If they're not, Duque says, they will be brought into the medical unit and detox prior to engaging in the programme.

Monday to Friday, the participants attend two workshops a day.

These workshops cover things like coping mechanisms, harm reduction, music therapy, mindfulness, and relapse prevention, he says.

They also learn to understand their own trauma, which may have occurred in childhood, and how that led to their addiction.

“The goal is to help them maintain and sustain a drug-free life,” says Duque.

Outside of the intensive TARP in Mountjoy, the prison service across the country has moved more towards group work in the last 12 months, says Mullins. That way, more people can be provided with supports.

This is considered very effective, he says, and mirrors the kind of addiction counselling that goes on outside of prisons in the community.

However, in Mountjoy, even group work has lengthy waiting lists.

“There's no doubt about it, there is a massive issue around addiction support in the prison system,” says Mullins.

The waiting list numbers for mental health and addiction supports in Mountjoy are stark and can never clear, says Keith Adams, the penal policy advocate at the Jesuit Centre for Faith and Justice.

“Policymakers propose that the solution is more resources. Undoubtedly this is needed but it's simply a band-aid,” he says.

“Genuine solutions can only be found when the mental health crisis is properly understood,” Adams said.

Duque says that, in the last few months, TARP has piloted the “care plan”.

This involves arming the participant with vital information to continue their progress inside or outside of prison.

This might involve helping them locate and engage with Alcoholics Anonymous or Narcotics Anonymous inside the prison where they are incarcerated.

For those facing the prospect of release, Duque’s team will link them in with counsellors outside and help them prepare to achieve their goals, like finding a job.

“Someone might want to get work on a building site, but they don’t know how to get a Safe Pass,” he says. “So we’ll go through all of that.”

This emphasis on connecting people with services outside in the community ahead of their release is gaining traction across the prison system.

As is the idea of peer-led recovery.

A spokesperson for the IPS said on Thursday that it is currently developing a new, bespoke model which aims to “provide for co-occurring difficulties associated with mental health and addiction and to support those leaving custody in engaging with the community and continued care on release”.

“The Irish Prison Service support a community-based approach to engaging with addiction in the prison population and link in with appropriate community services,” they said.

McEntee, the former Justice Minister, gave an identical statement in response to a parliamentary question almost two years ago.

There have been really positive developments but they are a long time coming, says Niall Hickey, a peer support worker with Uisce, an advocacy group for drug users in Ireland.

Hickey was incarcerated in various prisons throughout his life, he says. He was last released in 2013.

Now, he helps support people who have come out of prison using a valuable tool – his own experience, he says.

Back when he was last released, there were even fewer supports for people leaving prison, he says, and while finding your way outside remains incredibly challenging, it was even harder over a decade ago.

Mullins, former governor of Mountjoy, says that while things are on the right track, improvements can still be made on building pathways back into society.

“I've seen guys leave prison and rapidly, rapidly deteriorate back in the community, because the level of support isn’t there,” he says.

There is currently a “perfect storm” of issues facing the prison system, Mullins says.

Overcrowding has had an obvious, adverse impact on pathways to addiction and mental health treatment for incarcerated people, he says. As have prison staffing issues.

Due to overcrowding, people not deemed to be a danger to society are often given unplanned, temporary release after short periods, he says.

This leaves little time for meaningful recovery work in prison.

For those on shorter sentences, they may get an assessment and a referral onto a community programme by the likes of Merchants Quay or Anna Liffey Drug Project when released, he says.

However, on the outside, the homelessness crisis rages on. This, Mullins says, massively impacts those already suffering from addiction.

“So, a guy who comes out of prison who hasn't got a family to go to, who has had addiction issues, he really goes back into the eye of the storm very, very quickly and deteriorates very, very quickly,” he says.

The most recent data on prison reoffending says that 62 percent of people who were released from custodial sentences during 2018 were convicted of reoffending within three years of release.

Of people released in 2021, 42 percent reoffended within a year after being released from custody, it says.

Elizabeth Kiely, a senior lecturer in social policy at University College Cork and member of the Irish Prison Abolition Network (IPAN), said in July that homelessness is a major driver of people into criminality and imprisonment.

Further, the shortage of prison staff often means that many services are closed, Mullins says.

“If you're a prison governor, you go in in the morning, and you're supposed to have 150 staff, and you've only 100 staff, which wouldn't be unusual. You have to prioritise all of the security posts. You have to prioritise all of the escorts."

“So, you could find on any given day that all of the rehabilitation services, education work, training, addiction support, psychology, they're all closed,” he says.

Adams, the penal policy advocate at the Jesuit Centre for Faith and Justice, says the current waiting lists for supports constitute a crisis.

“What these figures also indicate is the deterioration of the person within an overcrowded prison,” he says.

“Many may not have arrived in prison with mental ill-health or addiction,” he says, “but the environment has nevertheless resulted in widespread conditions associated with despair.”

Funded by the Local Democracy Reporting Scheme.