On the walls of a Kilbarrack health centre, an artist pays tribute to the beautiful ordinary

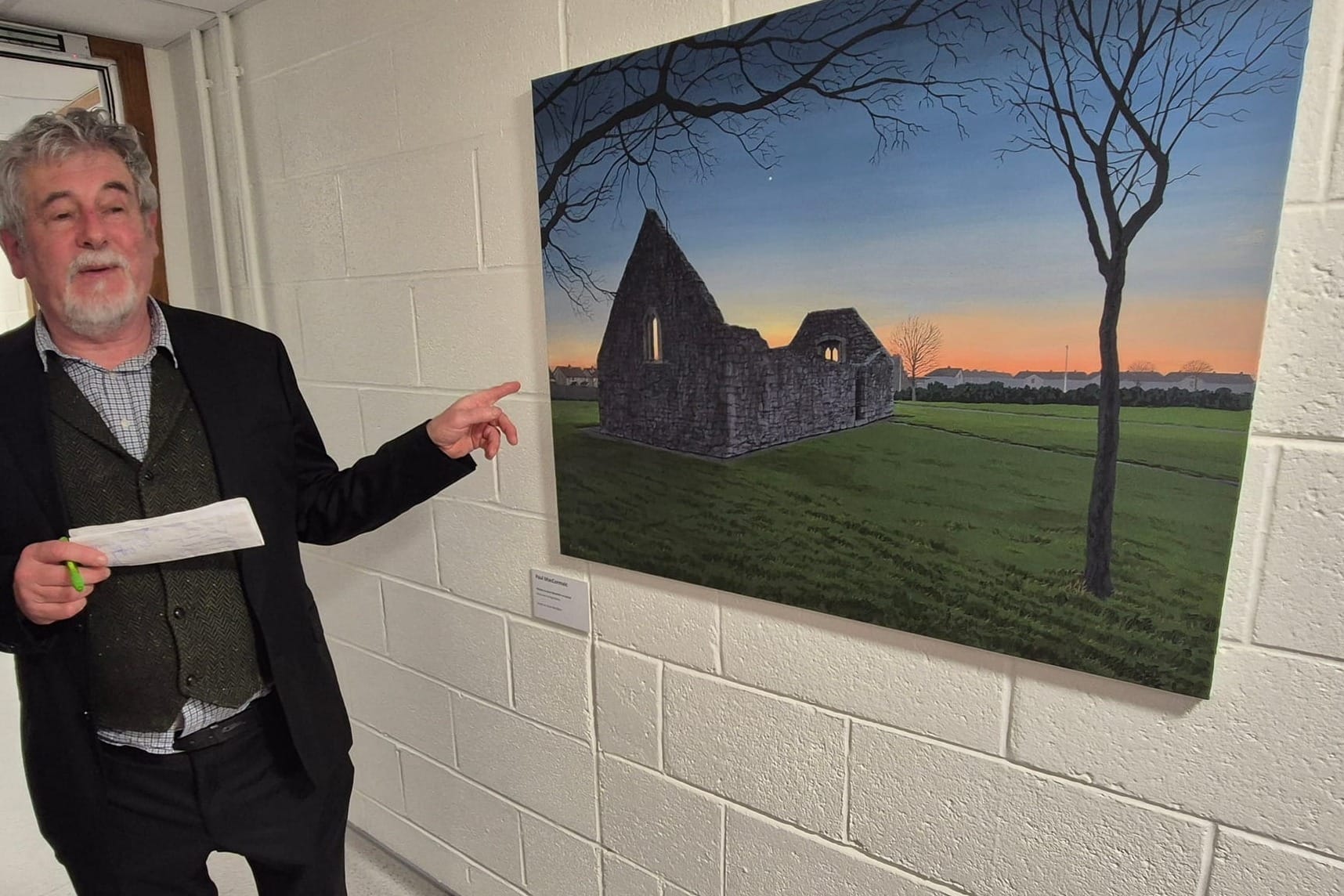

Paul MacCormaic says he hopes the works inspire an interest and pride in nearby sights, passed by everyday.

Paul MacCormaic says he hopes the works inspire an interest and pride in nearby sights, passed by everyday.

A large crowd gathered in Kilbarrack Health Centre on Wednesday night.

The ceiling was far above them. Some stood with necks stretched and heads tilted upwards at the tall white walls.

Two large paintings hung side by side.

One was of the nearby basketball courts at Coláiste Dhúlaigh, the other of Kilbarrack Dart Station viewed from the west.

“We won't usually come to this building to look,” said artist Jenny Walton, as she officially launched the exhibition.

“But this is a place where we will spend time, time where we're in particular emotional or physical states,” said Walton.

And with his paintings, with the light and the trees, Paul MacCormaic has brought the outdoors indoors, she said, and encourages a calm meditation.

Sixteen of MacCormaic’s paintings now hang in the new health centre in Kilbarrack, all pieces in a permanent exhibition titled Mo Cheantar Féin – My Own Area.

MacCormaic hopes the works inspire an interest and pride in the local environment, he says, to help people see the beauty in the mundane.

In her remarks, Walton stressed the same: “These sixteen paintings aim to transform ordinary, overlooked places into something monumental by removing them from their everyday context and presenting them as art.”

MacCormaic, who grew up in Finglas but lives in Kilbarrack, is known for his portraits.

His last solo exhibition, The Vanquished Writing History, ran at the Royal Hibernian Academy in Dublin for five weeks.

It featured portraits of campaigners and activists who have worked, in their own way, to make Ireland a better place, he says.

He painted Martin and Peggy Murphy, members of the Irish Thalidomide Association. And Antoinette Keegan, spokesperson for the Stardust Victims Committee.

So, followers may be surprised by the lack of people in this newest collection – although some do appear, fishing at the bottom of the Kilbarrack Road, or cycling along the coast.

But these are portraits nonetheless, he says. They are tree portraits. Rowan trees bright with berries. A crab apple tree in blossom.

As MacCormaic walks around the centre, he talks about each painting he passes. He wanted to document the ash tree in particular, he says.

Ash dieback, a serious disease, poses a grave threat to Ireland’s ash population, he said.

In capturing ash trees at St Donagh’s Estate, they stand immortal, he says.

“It’s the tree we make our traditional hurleys from,” says MacCormaic, standing by the painting in an upstairs hallway. “They have a bit of spring in them too so the hurley won’t break. It’s not brittle.”

MacCormaic also explores how light interacts with these seemingly ordinary scenes, to reveal the beautiful and everchanging – if you stop to look.

Walton, in her speech, had told those gathered to look closely at the painting of the basketball court in the main reception.

The painting captures the early evening light at the start of winter, she said. “Leaves are still on the trees, and there's long shadows across the ground.”

“The tall red hoops are matching the trees, and they catch the light in a completely different way to what is caught in the foreground there,” said Walton.

The Coláiste Dhúlaigh groundskeeper had thanked him after he saw the painting, MacCormaic said, jokingly. He told the artist that he made him look good because the grass was cut and there was no rubbish lying around.

MacCormaic said that he had enjoyed playing around in the night scenes with the throw of street lamps and red traffic lights. “The green grass becomes red.”

Early in the evening, MacCormaic thanked locals who made him aware of spots that he had never been, or noticed, before.

One was the Bayside Community Garden. “You can't get to it by car,” he said. “There's four little alleyways and you just walk through it. It's kind of hidden.”

Another small community garden had been pointed out to him by local activist Madeliene McNally-Murray, who was one of a small group who built it.

The Past, Present and Future Community Garden sits on Briarfield Grove. It holds several fruit trees.

The trees represent the people who have come before in the area, those there now, and those yet to come, he said.

Two smaller trees are dedicated to local man Lloyd Clarke. He was the first person from Briarfield Grove to donate organs, said McNally-Murray.

“He gave seven lives a new chance,” she said.

MacCormaic says the small garden was made all the more curious by the ordinariness of the terraced houses behind.

The night was poignant for McNally-Murray. MacCormaic had dedicated the event, and the exhibition, to her late-husband, Johnny.

He died of a heart-attack in January.

“He would have been here tonight. He was really, really keen,” said MacCormaic. “He didn't want to see them beforehand. He wanted to see them tonight as a special thing.”

Soon, they’ll add to the benches in the Past, Present and Future Community Garden, said MacCormaic. A new one, dedicated to Johnny, he said.

McNally-Murray carried a framed picture of her beloved husband in her hands for the evening.

On the wall at the top of a staircase in the Kilbarrack Health Centre hangs the largest of all the paintings – also of a staircase.

Another theme of the collection, says MacCormaic, is how nature wins back its territory.

How wild sporadic plant life contrasts with the rigid angles of houses and bridges, he says.

Eighteen Steps to Kilbarrack Lower depicts the stone staircase that leads from the Dublin Road down to the shoreline of Dublin Bay. Grass and wild daisies poke out of crevices around the steps.

This is also a special place for McNally-Murray, she says. It was where she and Johnny went on their first date.

The pair sat on the steps, chatting – and watching the rats, she says. “They’re intelligent creatures.”

Johnny was fascinated by them, she says, with a chuckle.

Mo Cheantar Féin is now a permanent exhibition in the Kilbarrack Health Centre.

Funded by the Local Democracy Reporting Scheme.